Easy Questions about Dubins Paths

This post is about Dubins path planning; see the previous post here (Dubins Corner Revisited) for context and application for the following problems. With the resolution of the following lemmas, the proof of the Dubins' corner problem in the previous post will be compete.

The term "Easy" should not be taken in the pejorative sense. Instead, they are path planning problems with simple statements and simple answers. In fact, the shortest path in each case will be so blatantly obvious that it almost does not need a proof. On the other hand, I have failed to supply the kind of one-line proof that my expectation of elegance demands, which makes these problems excellent candidates for the sort of informal minimal-proof competitions that math students tend to enjoy. I also have a lingering interest in keeping the following arguments as elementary as possible. I have managed to avoid using any result specific to Dubins path planning at all, notably the characterization of shortest Dubins paths on a plane. This further signifies that the Dubins Corner problem is in fact very "easy".

Question #1: Shortest Path to a Line

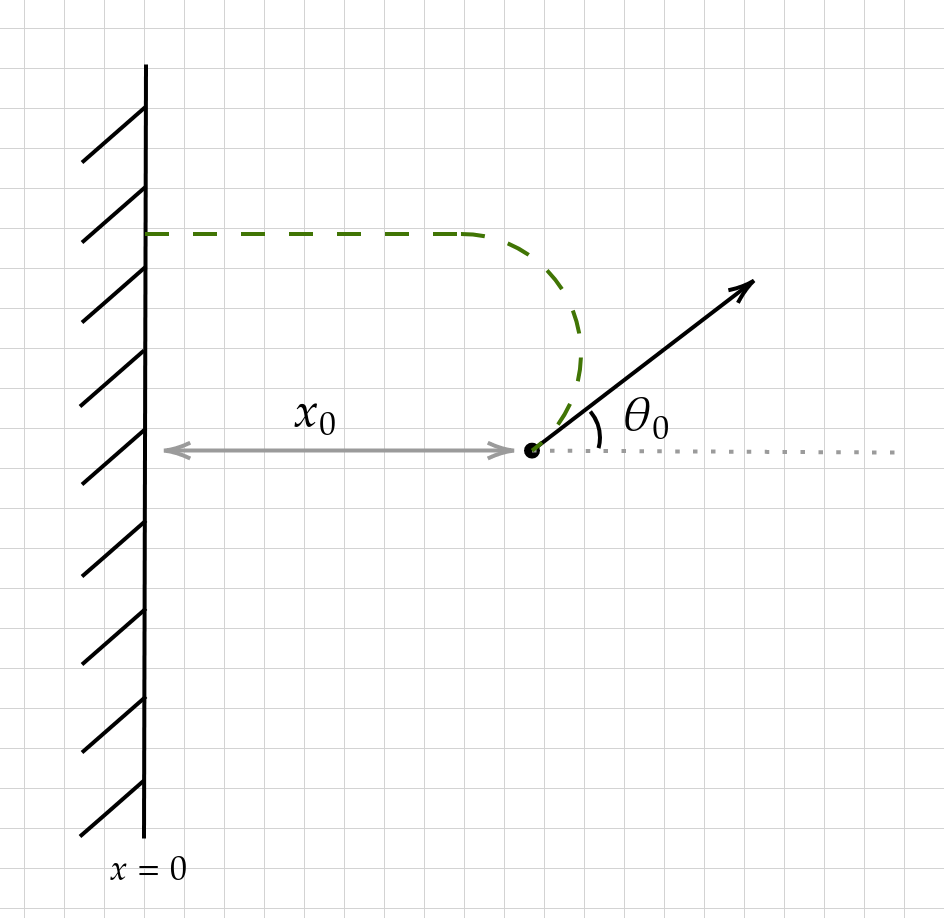

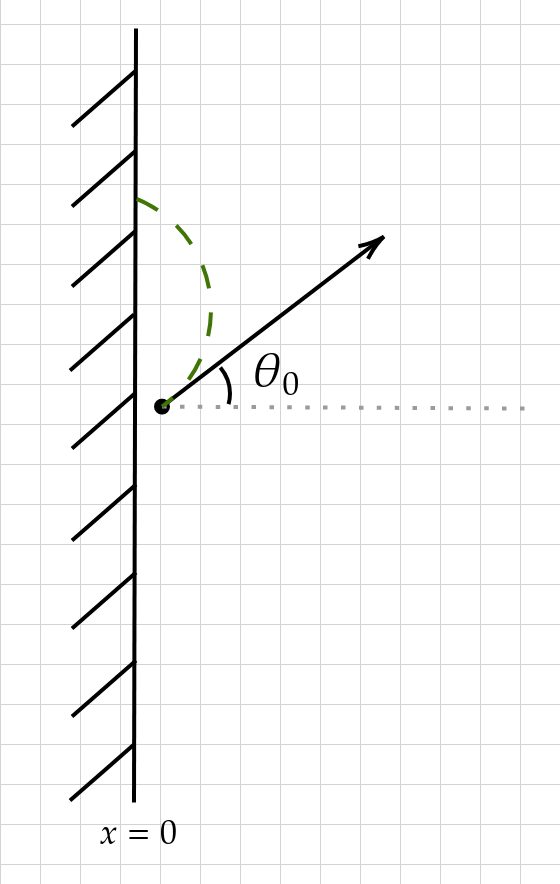

(Shortest Path to a Line) Let \((x_0,y_0)\in \mathbb{R}^2\) be the initial position of a Dubins car, \(x_0>0\), and \(\theta_0\in [0, 2\pi)\) be the initial orientation of the car, measured as an angle from the positive \(x\)-axis. The shortest path from \((x_0,y_0,\theta_0)\) to any point on the \(y\)-axis is formed by an arc of radius 1, possibly followed by a line parallel to the \(x\)-axis. If \(\theta_0\in (0,\pi)\), the arc is a left turn, if \(\theta_0\in (\pi, 2\pi)\) the arc is a right turn. If \(\theta=0\), both a left and right turn yield shortest paths (the unique case of multiple solutions), otherwise if \(\theta=\pi\) the arc has zero length. The car follows the arc until it either hits the \(y\)-axis or becomes parallel to the \(x\)-axis, whichever comes first. If it has not hit the \(y\)-axis, then it continues straight until it does.

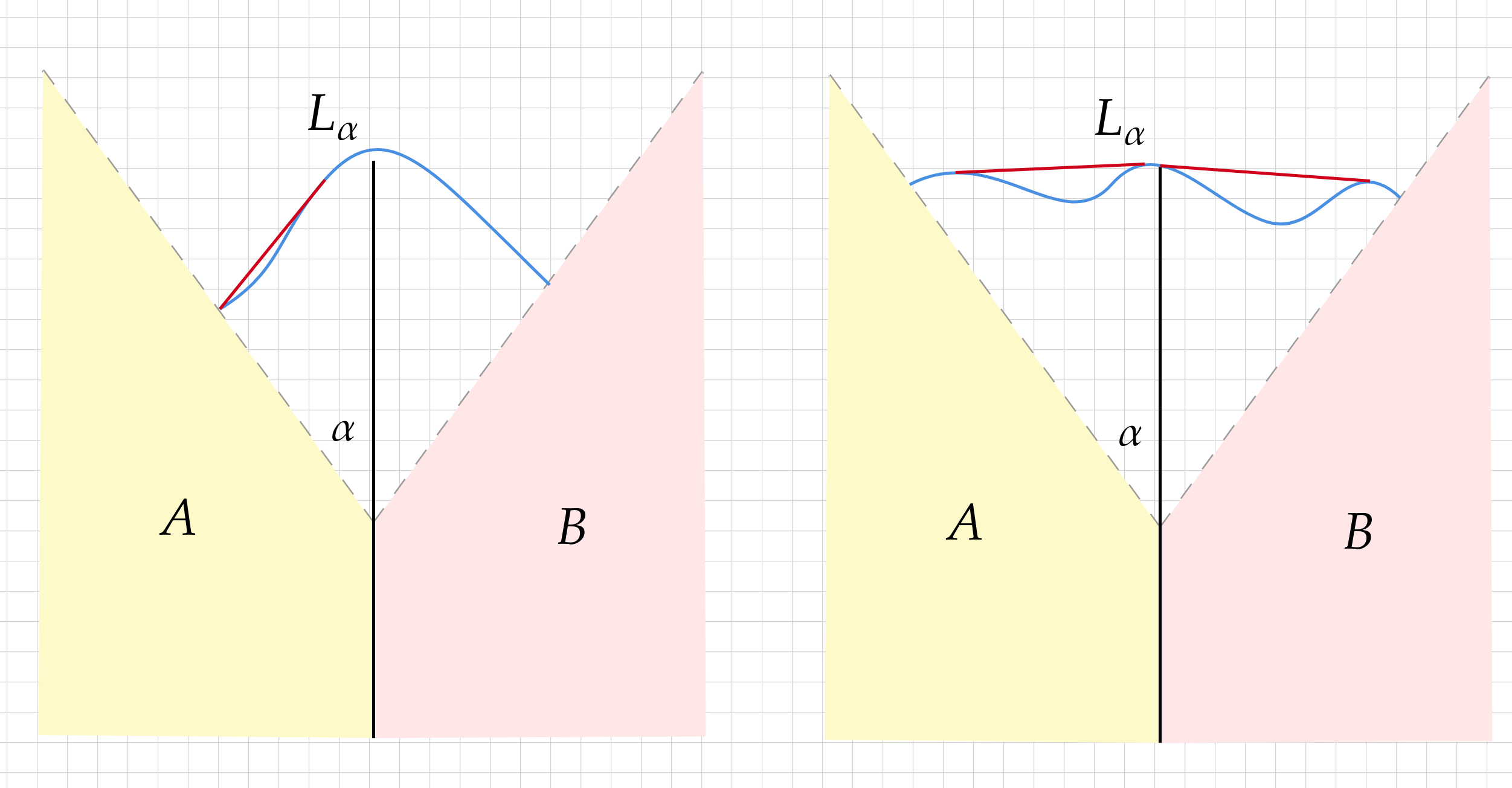

The images above illustrate the solution. The shortest path is essentially a greedy path on \(\theta(t)\), achieving and maintaining \(\theta(t)=\pi\) as quickly as possible. This will be the substance of our proof below.

Proof. Let \(\theta(t)\) be the angle of the Dubins car at a time \(t\). We seek an assignment of \(\theta(t)\) so that \[x(t)=x_0+\int_0^t \cos(\theta(s))\,ds\] is zero as quickly as possible. Let \(\widehat{\theta}(t)\) be the angle of the proposed optimal path, and \(\theta(t)\) be another Dubins path. Since \(|\widehat{\theta}'(t)| \leq 1\) (radius restriction), the function \(|\pi-\widehat{\theta}(t)|\) is pointwise less than or equal to \(|\pi - \theta(t)|\). Thus \[ \begin{align*} \cos(\widehat{\theta}(t))&=-\cos(\pi-\widehat{\theta}(t))=-\cos(|\pi-\widehat{\theta}(t)|) \\ &\leq -\cos(|\pi-\theta(t)|)=-\cos(\pi-\theta(t))=\cos(\theta(t)) \end{align*}\] and \[\int_0^t \cos(\widehat{\theta}(s))\,ds \leq \int_0^t \cos(\theta(s))\,ds\,.\] This shows that \(\widehat{\theta}\) is optimal. If \(|\pi-\theta(t)|\) is strictly greater than \(|\pi-\widehat{\theta}(t)|\) for some \(t\), then there is some \(t\) for which \(\cos(\widehat{\theta}(t))\) is greater than \(\cos(\theta(t))\) so that, by continuity, \[\int_0^t \cos(\widehat{\theta}(s))\,ds \lneq \int_0^t \cos(\theta(s))\,ds\,.\] If \(\theta_0\neq 0\), then \(|\pi-\theta(t)|=|\pi-\widehat{\theta}(t)|\) implies that \(\theta(t)=\widehat{\theta}(t)\) by continuity. Considering \(\theta=0\) easily shows the two optimal paths which are mirror images of each other. (QED)

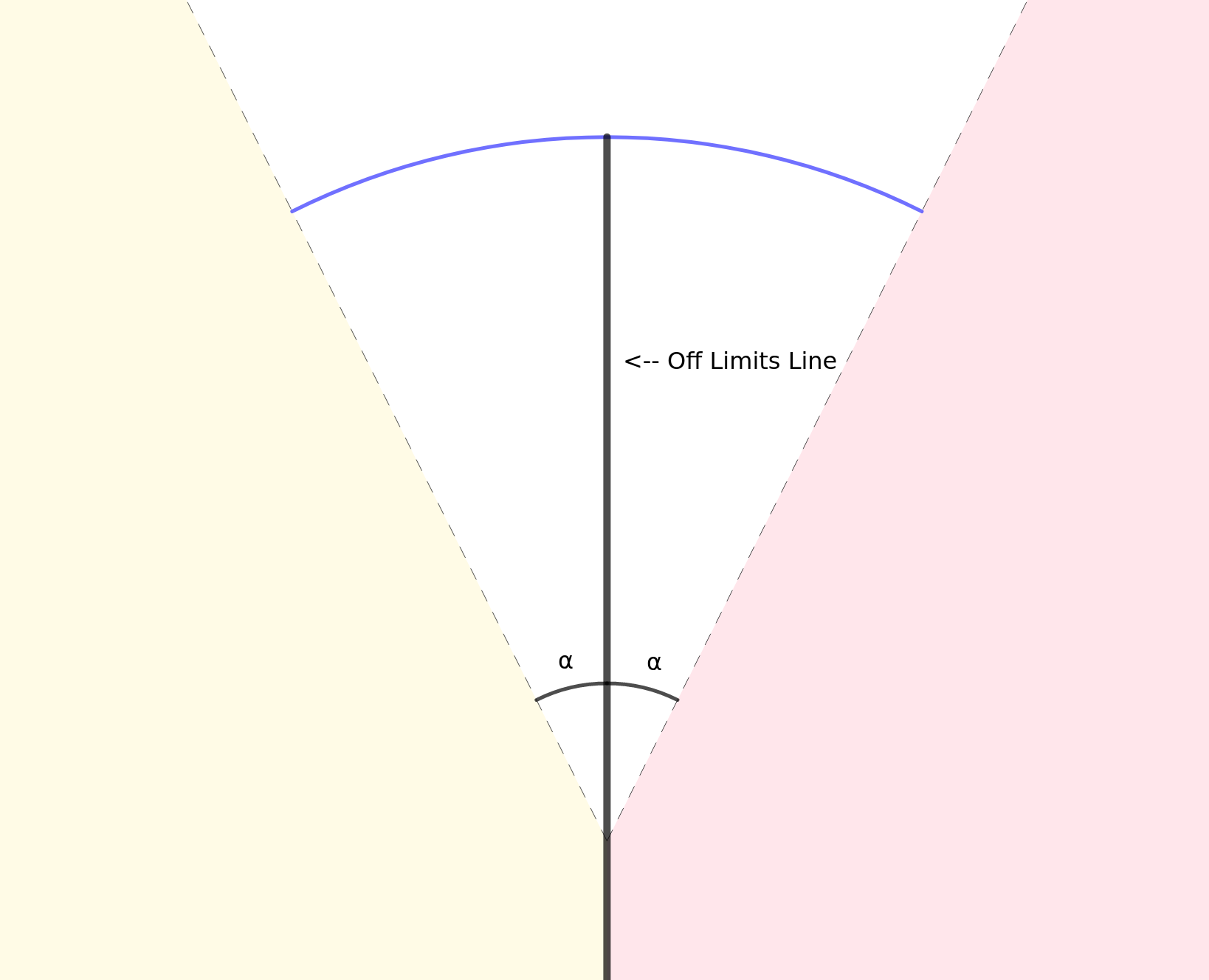

Question #2: Shortest Path Through a Sector

(Shortest Path Through a Sector) Consider two regions \(A=\{x\leq 0, x\leq \tan(\alpha)y\}\) and \(B=\{x\leq 0, x\leq -\tan(\alpha)y\}\) on the plane. The shortest Dubins path from \(A\) to \(B\) avoiding the line \(\{x=0,y<1\}\) is a circular arc passing through the point \((0,1)\) perpendicular to the bounding lines.

This situation is illustrated in the above picture. As is standard (and without loss of generality), we assume a minimum turning radius of 1. We'll bound \(\alpha\) by \(\pi/2\).

Proof. We will first establish two basic characteristics of a shortest path:

- A shortest path passes through the point \((0,1)\)

- A shortest path does not contain any left turn, if viewed as a path starting from the left side.

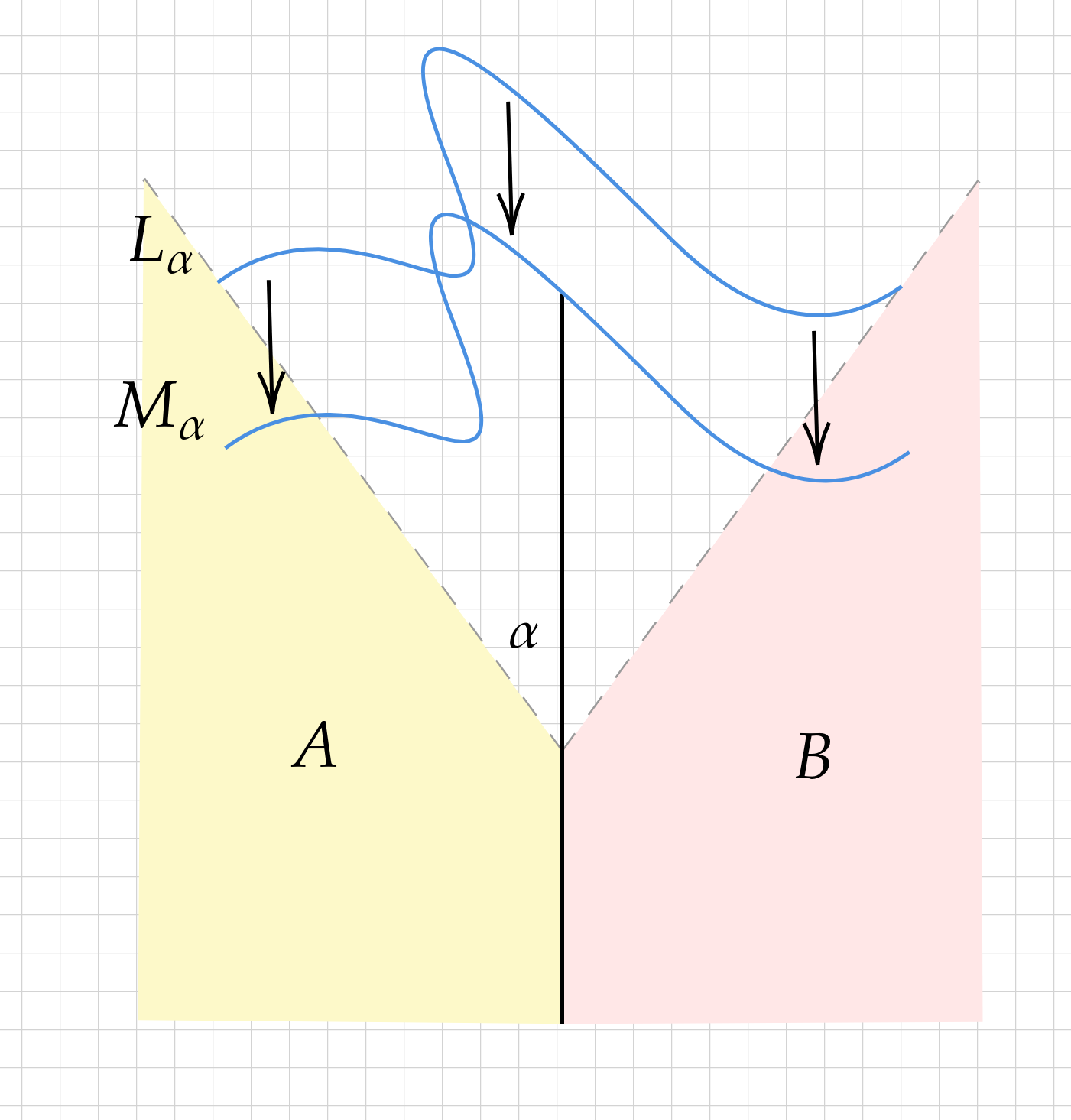

For (1), if \(L_\alpha(t)\) does not pass through \((0,1)\), then \(\epsilon = \inf \{L_\alpha(t)_y - 1 : L_\alpha(t)_x=0\} \) is positive since \(L_\alpha\) traces a compact set in \(\mathbb{R}^2\). Then the translated path \(M_\alpha(t)=L_\alpha(t)-(0,\epsilon)\) avoids the obstacle and is strictly shorter than \(L_\alpha\), since \(M_\alpha(0)\) lies to the left of the line \(x=-\tan(\alpha)y\) (as the right endpoint lies to the right of the line \(x=\tan(\alpha)y\)). See Figure 1 below.

For (2), if \(L_\alpha(t)\) makes a left turn anywhere along its path, then there is a shorter path on the exterior (i.e. farther from the origin) side of \(L_\alpha\) that skips the left turn. Formally, this is only the statement that the convex hull of \(L_\alpha\), (on the exterior side) is shorter than \(L_\alpha\) and a valid path. It is a valid Dubins path because it coincides with \(L_\alpha\) whenever it contains a curve. It is shorter because the connections between those curves (or the endpoints of \(L_\alpha\)) are the shortest possible. A picture is most illustrative here; see Figure 2 below.

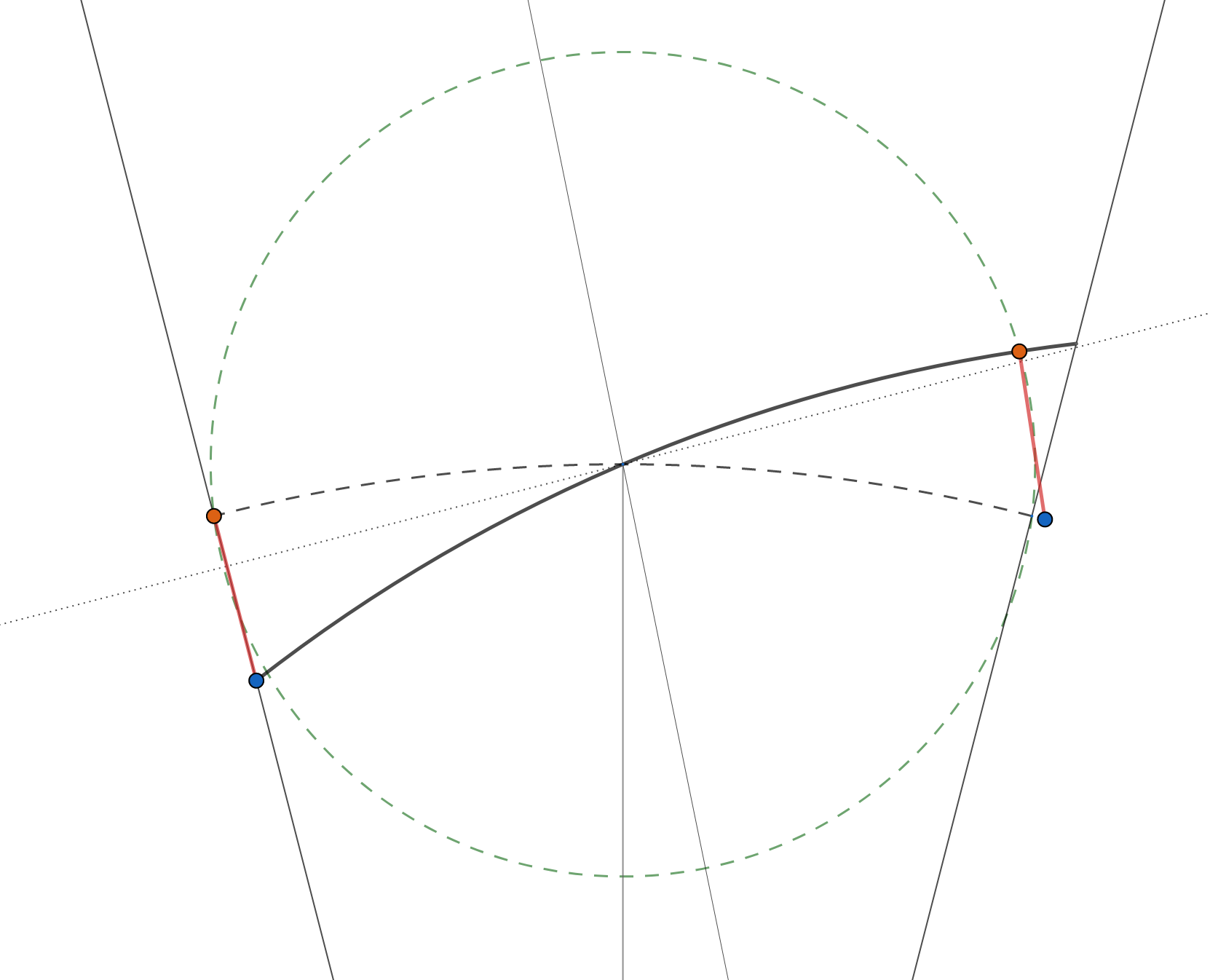

We are now ready to tackle the problem. The optimal path meets \((0,1)\) at some angle, WLOG with non-negative slope. Assume for the sake of contradiction that the optimal path meets \((0,1)\) with positive slope, to differentiate it from the standard, circular sector path. To the right of \((0,1)\), the path turns right until it meets the right wall or is perpendicular, according to Question #1. To the left of \((0,1)\), the path lies above a constant right-turn path (solid black line in Figure 3), above a line perpendicular to the left wall passing through \((0,1)\) (there are no left turns allowed), but below the standard sector path (dashed black line in Figure 3). It must be below the standard sector path because we know the behavior of the optimal path by Question #1: it must curve toward the left wall until it hits the wall or reaches perpendicularity.

Now we note that the area between the standard sector path (above) and posited optimal path (below) to the left of \((0,1)\) is strictly less than the area between the standard sector path (below) and posited optimal path (above) to the right of \((0,1)\). This can be seen by reflecting the area on the left across the line of symmetry (thin vaguely-vertical line in Figure 3 which is a diameter of the green circle). Since the area on the left is entirely contained within the green dashed circle, its reflection is entirely contained within the right area.

This means that the total area under the posited optimal path is strictly larger than \(\alpha\), the area under the standard sector path. A direct application of the isoparametric inequality for sectors (see here for example) shows that the posited optimal path has length larger than \(2\alpha\). Since the standard sector path has length exactly \(2\alpha\), this means that our posited optimal path is, in fact, not the shortest.

We conclude that the unique shortest path is the standard sector path, a circular arc perpendicular to the boundaries that passes through \((0,1)\). (QED)

Several diagrams made with Geogebra.