Dubins Corner Revisited

There is a subfield in robotics that concerns itself with so-called "non-holonomic motion planning." Motion planning is essentially the study of how to get robots from point A to point B in an environment, with the "non-holonomic" descriptor targeting robots that have non-trivial motion rules.

For example, you might wish for an RC car to correctly traverse a maze. A solution — that is, a set of movements for the RC car — must not only "solve" the maze in the conventional sense, but do so in a way that respects the car's inability to move sideways (for example). An RC car is non-holonomic since its direction of movement is not completely free; it depends on what direction the car is facing.

There is a further subfield in non-holonomic motion planning that restricts itself to the motion planning of an idealized robot called the "Dubins Car". Named after the mathematician Lester Dubins, this is a robot that traverses \(C^1\) (and almost-everywhere \(C^2\)) paths of the form \[ \left\{L(t):\mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}^2:|L'(t)|=1\text{ and } |L''(t)|\leq 1 \right\}\,. \] This is a point robot constantly moving forward, having a minimum turning radius of 1. Dubins' original 1957 paper detailed the optimal trajectory of such a robot to minimize the total distance traveled between two "poses," an initial pose \( (p_i, \theta_i) \) and final pose \( (p_f, \theta_f) \), each giving the position \(p \in\mathbb{R}^2\) and orientation \(\theta\in [0,2\pi)\) of the robot. Dubins' results can be (inexhaustibly) summarized:

- The robot should either go straight or turn with radius 1 always. In other words, \( |L''(t)|\in \{0,1\} \).

- The optimal path between poses (with no external obstacles) consists of no more than three segments, with each segment either straight (S), a right turn (R), or a left turn (L). It is common to refer to these paths by their constituent parts. A "RSL" path, for example, consists of first a right turn (of minimal radius of course), followed by a straight section, and finally a left turn.

- Only paths of the form LRL, RLR, LSR, RSL, RSR and LSL can be optimal, up to degeneracy.

- Extensions of Dubins results. Some of these are the most well known, including the Dubins Airplane, and the Reeds-Shepp Car. Other extensions allow a range of initial/final poses, for example.

- Different proofs of Dubins' original result. There are surprisingly many of these.

- Algorithms for approximating shortest paths in the presence of obstacles. This is by far the most popular, since it is most topical to the end goal of motion planners.

Why do I know (or care) about Dubins cars? Back at university, I joined the robotics lab RSN at UMN on a summer REU. Being somewhat uninterested in robotics, Dubins path planning was most palatable since I could study it almost exclusively as a math problem. Thus I spent the summer of 2018 developing what I can only describe as a particularly inelegant proof of the optimality of a certain class of paths for a Dubins car turning a corner, as if in a hallway (perhaps undeservedly accepted to ICRA 2019, free access here). Although much work has been done approximating optimal Dubins paths with obstacles, few papers have attempted to find explicit solutions for prototypical examples.

As evinced by the length and complexity of my paper, I concluded that such explicit solutions were, by and large, difficult. However, lately I have come across a much simpler proof which I will show here.

The Dubins Corner Problem

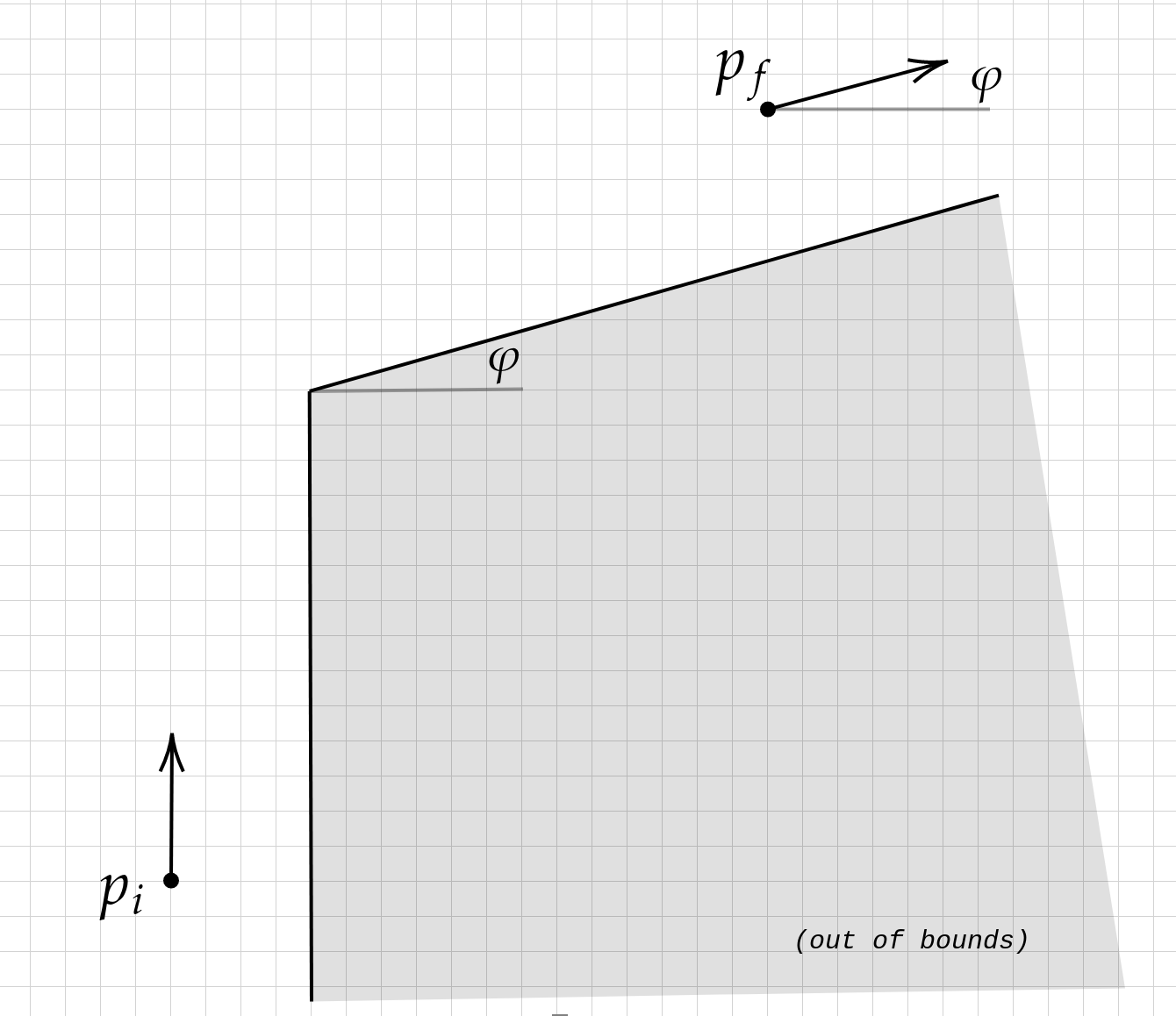

The problem is to find the shortest Dubins path from \(p_i\) to \(p_f\) around an interior corner

with angle \(\varphi\) (as in the above diagram).

The solution in most cases is rather predictable, consisting of two three-segment Dubins paths joined at the inner corner.

These paths are in the form RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR, and LSRSL, and may in general be parameterized by the angle made at

the inner corner.

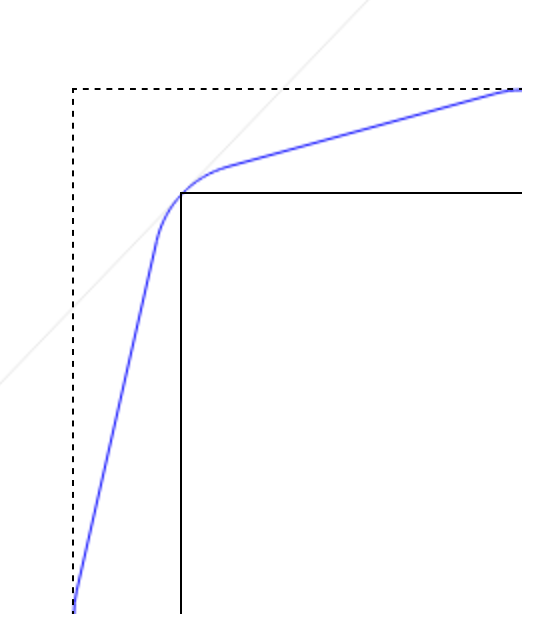

I've included a diagram below for a 90 degree corner, to show you how simple this is. (This is an RSRSR path).

The problem is to find the shortest Dubins path from \(p_i\) to \(p_f\) around an interior corner

with angle \(\varphi\) (as in the above diagram).

The solution in most cases is rather predictable, consisting of two three-segment Dubins paths joined at the inner corner.

These paths are in the form RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR, and LSRSL, and may in general be parameterized by the angle made at

the inner corner.

I've included a diagram below for a 90 degree corner, to show you how simple this is. (This is an RSRSR path).

Please note that my paper also includes some "outer walls" of the hallway, among other features. I have found these to be primarily clutter that distracts from the main problem I wish to exhibit. However, the outer walls do contribute to the solution in some cases and are of some interest. Perhaps I will address them later.

My paper made the following claim, slightly abridged for clarity:

(Alan's Theorem) If there exists any RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR or LSRSL path from \(p_i\) to \(p_f\) with middle R segment passing through the inner corner, then the optimal solution is either an elementary Dubins path from \(p_i\) to \(p_f\), OR an RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR or LSRSL path.

Here an "elementary Dubins path" is one of the three-segment paths originally formulated by Dubins to be optimal on the plane.

The New Proof

The main idea is that the class of optimal solutions {RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR, LSRSL} corresponds to a greedy-choice path planning through carefully chosen regions around the corner. The method is relatively simple:

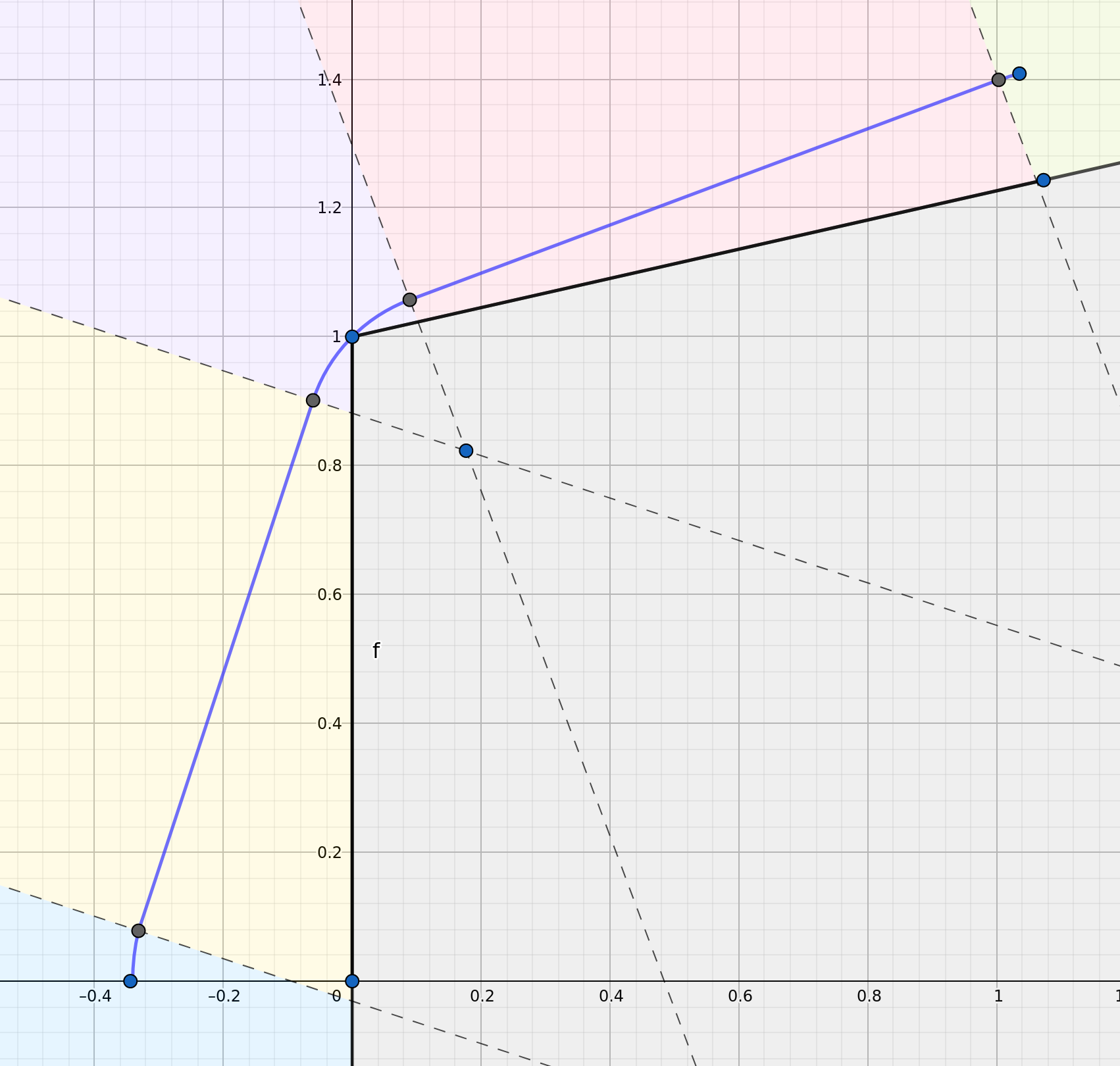

- Choose four lines that partition the corner into five disjoint regions so that any path must traverse the regions in order (see diagram below).

- Find the minimal-length Dubins path between successive lines.

- Show that the optimal RSRSR, RSRSL, LSRSR and LSRSL paths consist of the locally-shortest paths constructed in (2).

The above image (credit to Geogebra for diagram creation) shows five regions within the available environment: blue,

yellow, purple, red and green.

Clearly, a Dubins path (blue line) must pass over the blue region before entering the yellow region, pass over the yellow

region before entering the purple region, pass over the purple region before entering the red region, and

finally pass over the red region before entering the green region, where it may terminate at the end pose.

The above image (credit to Geogebra for diagram creation) shows five regions within the available environment: blue,

yellow, purple, red and green.

Clearly, a Dubins path (blue line) must pass over the blue region before entering the yellow region, pass over the yellow

region before entering the purple region, pass over the purple region before entering the red region, and

finally pass over the red region before entering the green region, where it may terminate at the end pose.

Provided that the dotted lines are perpendicular to the Dubins path in question, it is certainly true that the Dubins path contained in the blue region is the shortest Dubins path to start at the beginning pose and reach the yellow region, as the Dubins path contained in the green region is the shortest to start in the red region and reach the final pose. Likewise, the part of the Dubins path contained within the yellow region is a shortest Dubins path which starts in the blue region and reaches the purple region, as is the Dubins path contained in the red region.

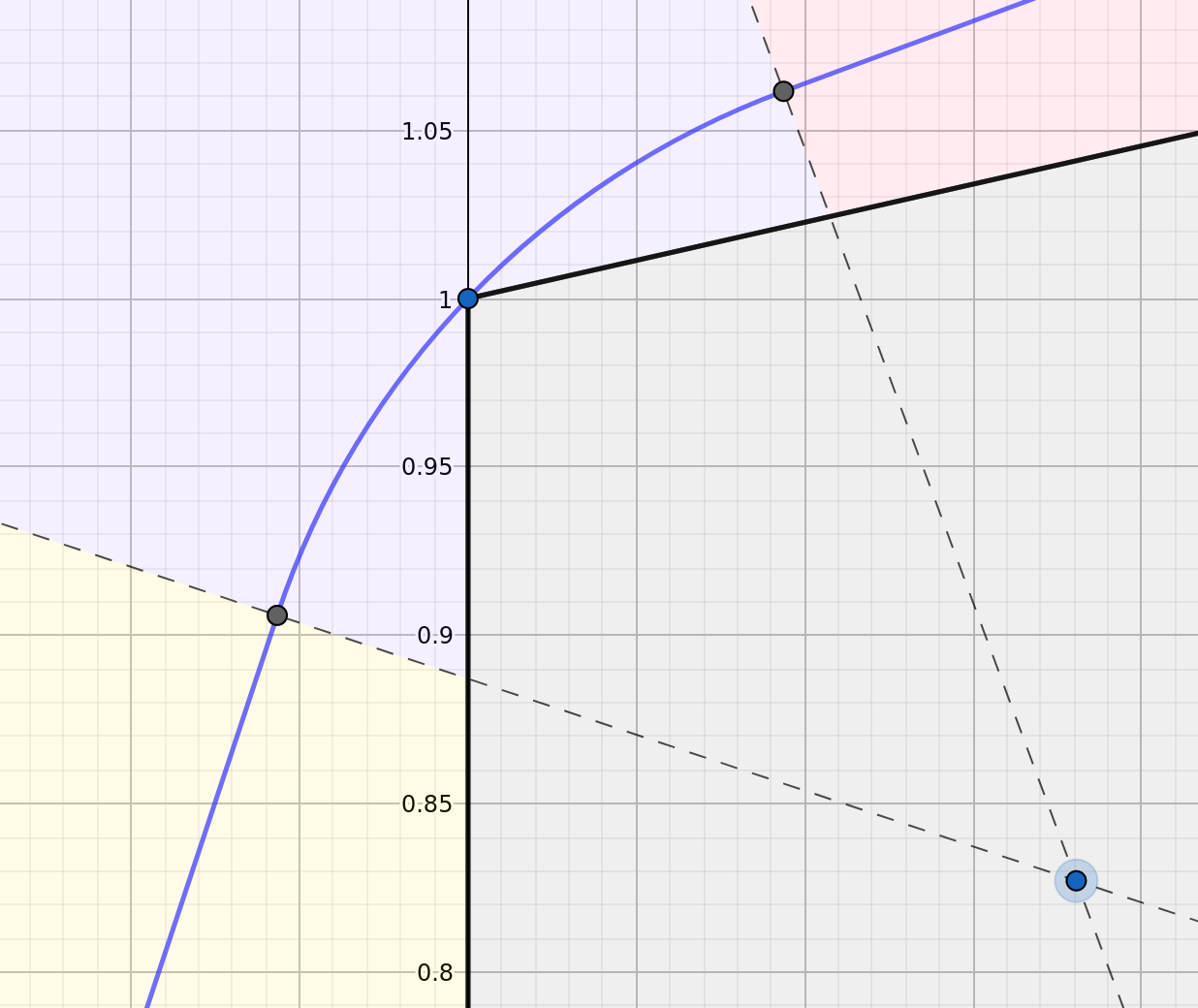

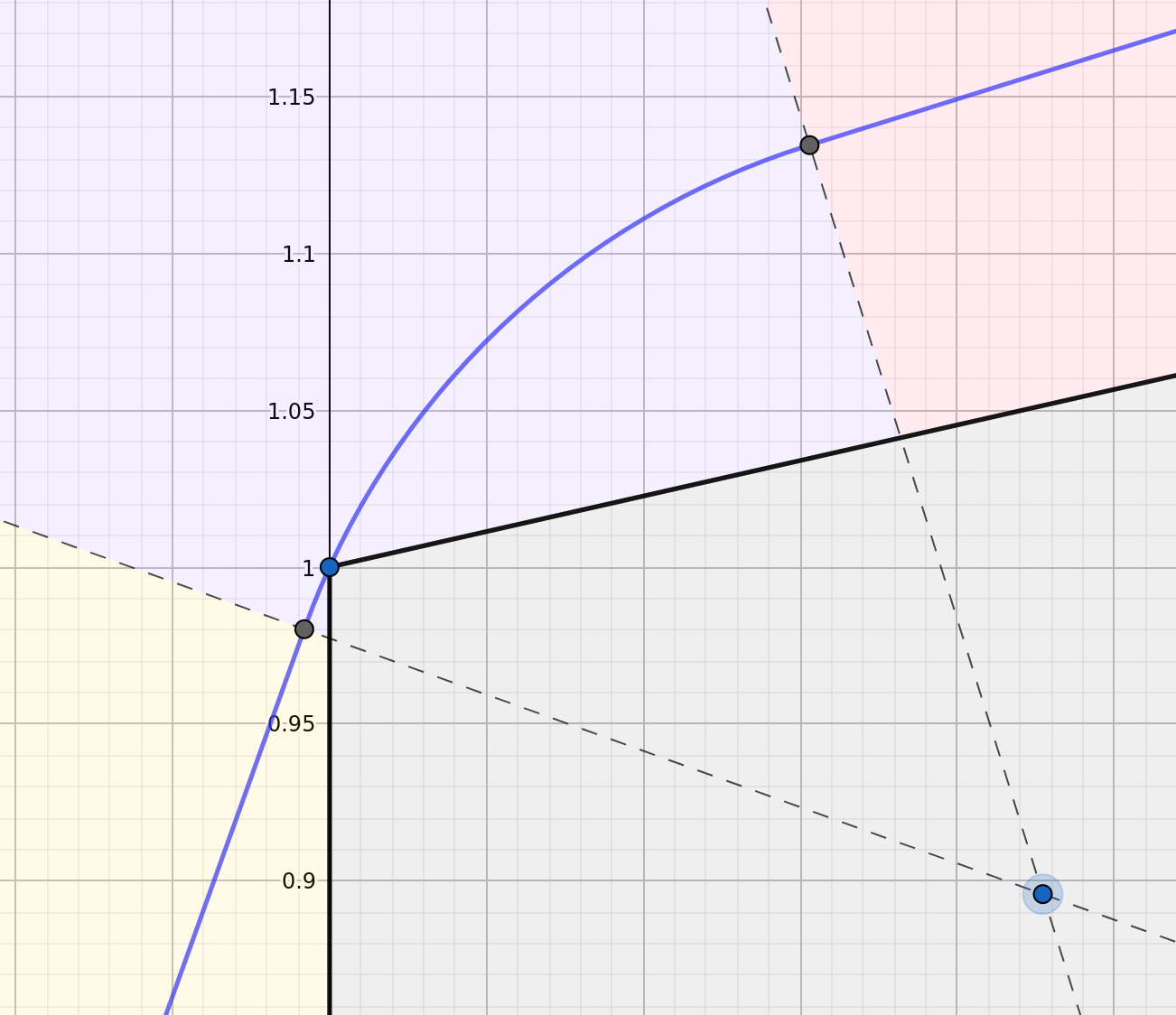

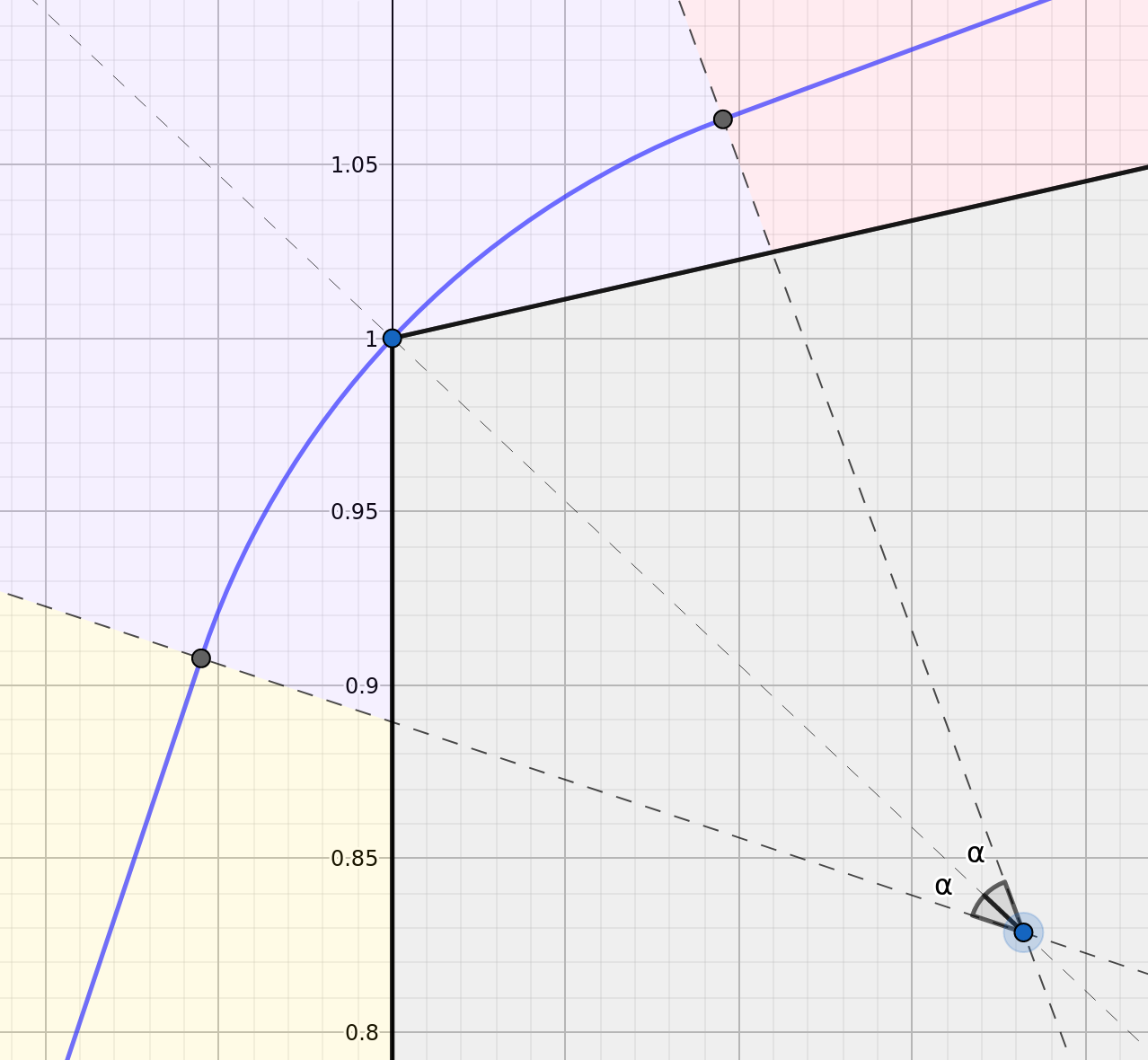

Our proof would be complete (at least for the RSRSR case, though RSRSL, LSRSR and LSRSL are basically identical) if we showed that the Dubins path contained in the purple region, passing through the inner corner, is the shortest Dubins path from any point in the yellow region to any point in the red region. Things get interesting here, because there are many different RSRSR paths passing through the inner corner, parameterized by the center of the arc of the second right turn. The figure below shows three of these configurations.

In the first and third images above, the blue path is clearly not the shortest between the yellow and red regions; a straight line would do better. The second is more convincing, but we'll need justification.

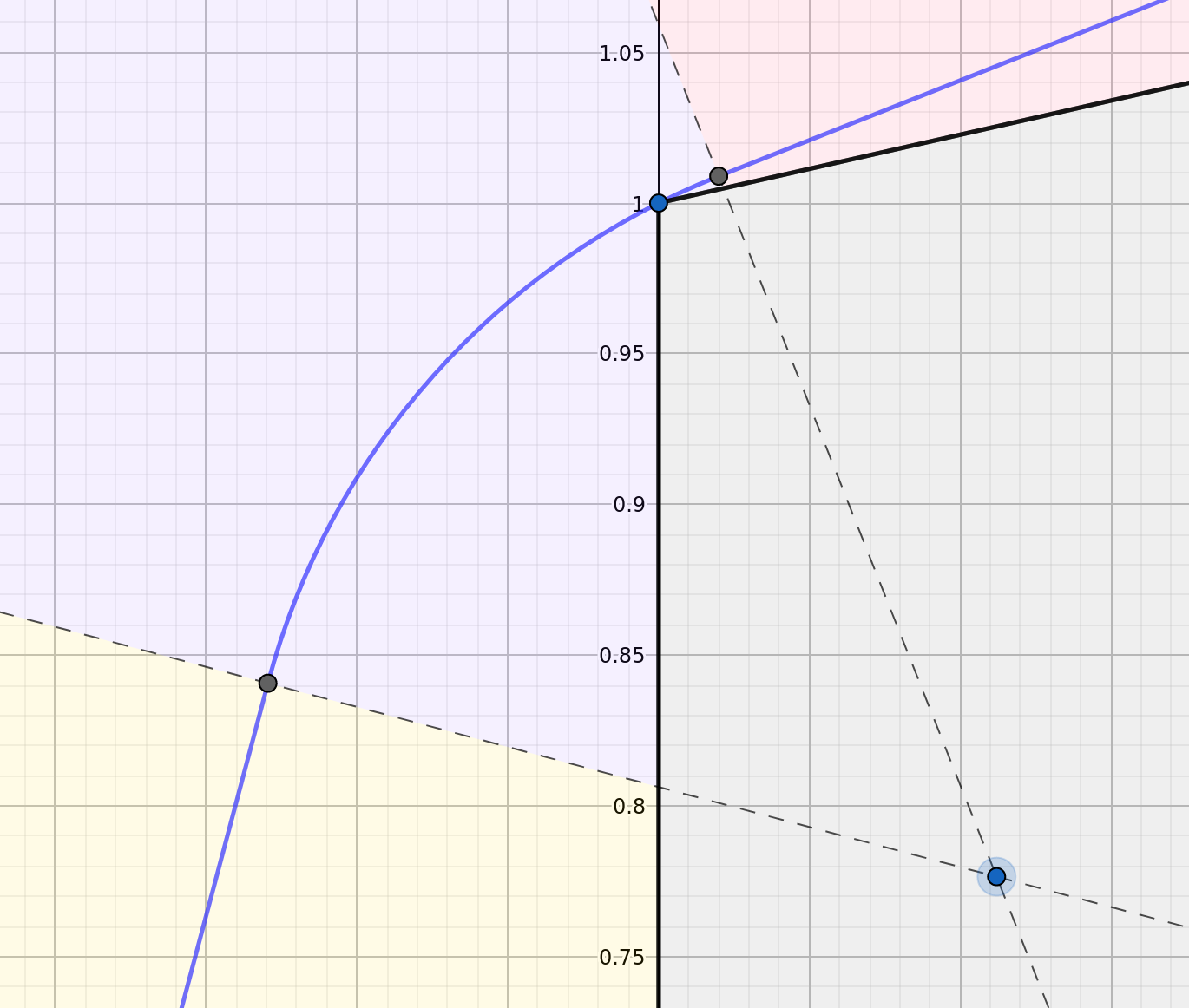

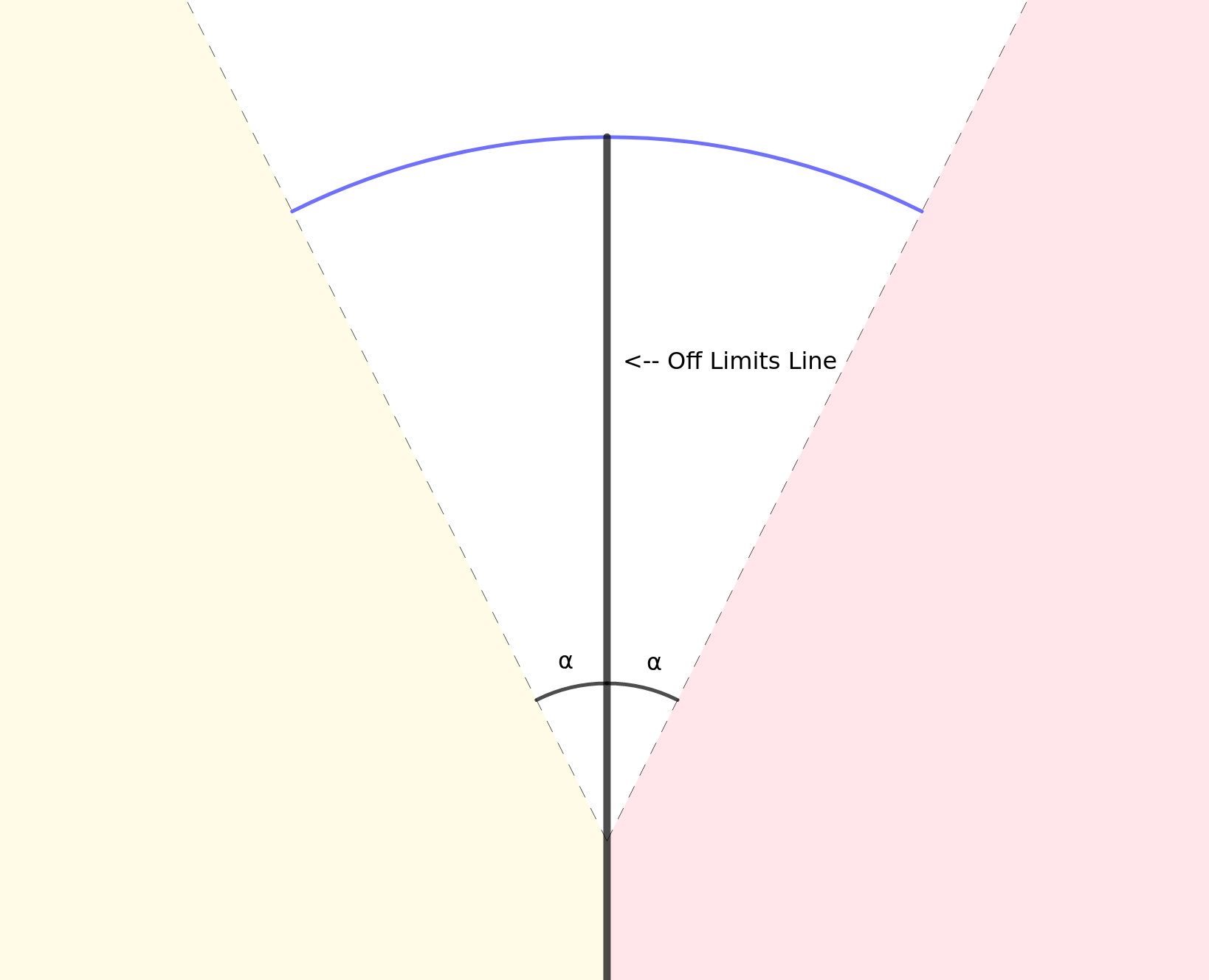

We make the following claim: if the length of the R curve between the yellow/purple boundary and the interior corner is equal to the length of the R curve between the interior corner and the purple/red boundary, then the R curve in the purple region is the minimum-length Dubins path from the yellow region to the red region avoiding the out-of-bounds. Since we can control the ratio between lengths before and after the corner by changing the center of the R arc, we can make this ratio 1 in the general case. (When we cannot, the path "lifts off" from the corner and becomes a "primitive" Dubins path of type RSL, RSR, LSL or LSR). To make this existence argument precise, some relatively easy continuity arguments are required; I'll leave that as an exercise to the reader.

The left image above shows the optimal configuration, equating the lengths in the purple region before and after the corner. Our job is to show that the blue path contained in the purple region (in this configuration) is the shortest Dubins route between any point in the yellow region and any point in the red region. The right image shows an equivalent formulation, again with the goal to show that the shortest Dubins route between the yellow and red regions follows the blue circular arc. Why is this equivalent? Suppose we find a shortest Dubins path \(L\) through some region with out-of-bounds zone \(A\). Suppose also that this path does not intersect some larger out-of-bounds zone \(B\supset A\). Then it must be that \(L\) is a shortest path through the region given out-of-bounds zone \(B\), since introducing more obstacles cannot possibly result in a shorter path. Here the set \(A\) is the line in the right picture; \(B\) is the gray region in the left, minding the rotation.

This equivalent formulation is clear enough so that it is obvious the blue path is shortest; however proving this fact in a number of words matching its perceived simplicity is a little tricky. I will address this and similarly "easy" problems in my next post here.