II. Exact Arithmetic

This is part II of the series A Practical Guide to Boolean Operations on Triangle Meshes. Part I on interval arithmetic can be found here.

In our last installment, we presented interval arithmetic as part of the solution for the problem of floating point error accumulation. To review, an arithmetic operation on a CPU has associated floating point error because of limited precision. Small errors in calculations can balloon into large errors in decision making given the right circumstances; if there's anything that we've collectively learned as programmers, it's that the right (wrong) circumstances are essentially inevitable. To remedy this, we adopt the following scheme:

- Compute arithmetic expressions using interval arithmetic, yielding rigorous lower and upper bounds for the result of the calculation.

- If we can't make a decision because the resulting interval is ambiguous, repeat the calculation using increased precision or exact arithmetic.

Number Representations

There are a lot of real numbers (aka "infinite decimals"). Almost all of them are "non-computable," meaning that we can't come up with any sort of finite representation for them. In other words, they will never be used, listed or uniquely described by anything or anyone. It's not as if we just choose not to use them; we are actually incapable of distinguishing them from the vast swaths of other nearby numbers in a finite amount of time and space. These numbers are by definition boring. If there was something uniquely interesting about a particular number, we'd need only articulate the fact and the number would be computable (in an informal way, for any math readers out there). For example, we care about \(\pi\) for many reasons, one being that it is the sum of the infinite series \[4\left(1-\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{5}-\frac{1}{7}+\frac{1}{9}-\ldots \right)\,. \] This is a representation that we can use to generate digits of \(\pi\). We can't generate all the digits of \(\pi\), but we can generate as many as we want given enough time and resources. Of course, we can't point out any particular non-computable number to you in a concrete and satisfying way. That would make it computable!

Academics love to start off their papers talking about "computable numbers," and for good reason. It is an impossible goal to attempt to create a representation for arbitrary real numbers on a finite computer. Instead, library designers must restrict themselves to smaller subsets of \(\mathbb{R}\). What subset depends on what you need from your exact arithmetic library. Let's give an example.

Example Number Representation: Algebraic Numbers

Algebraic numbers are exactly the numbers that are roots of polynomials with rational coefficients. Any number that can be written as an expression using rational numbers, basic operations (\(+\), \(-\), \(\times\), \(/\)) and radicals is algebraic, though there are many algebraic numbers that cannot be written like this. Compass and straightedge construction is a classic application of algebraic numbers, with each point coordinate equal to some expression involving addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square roots.

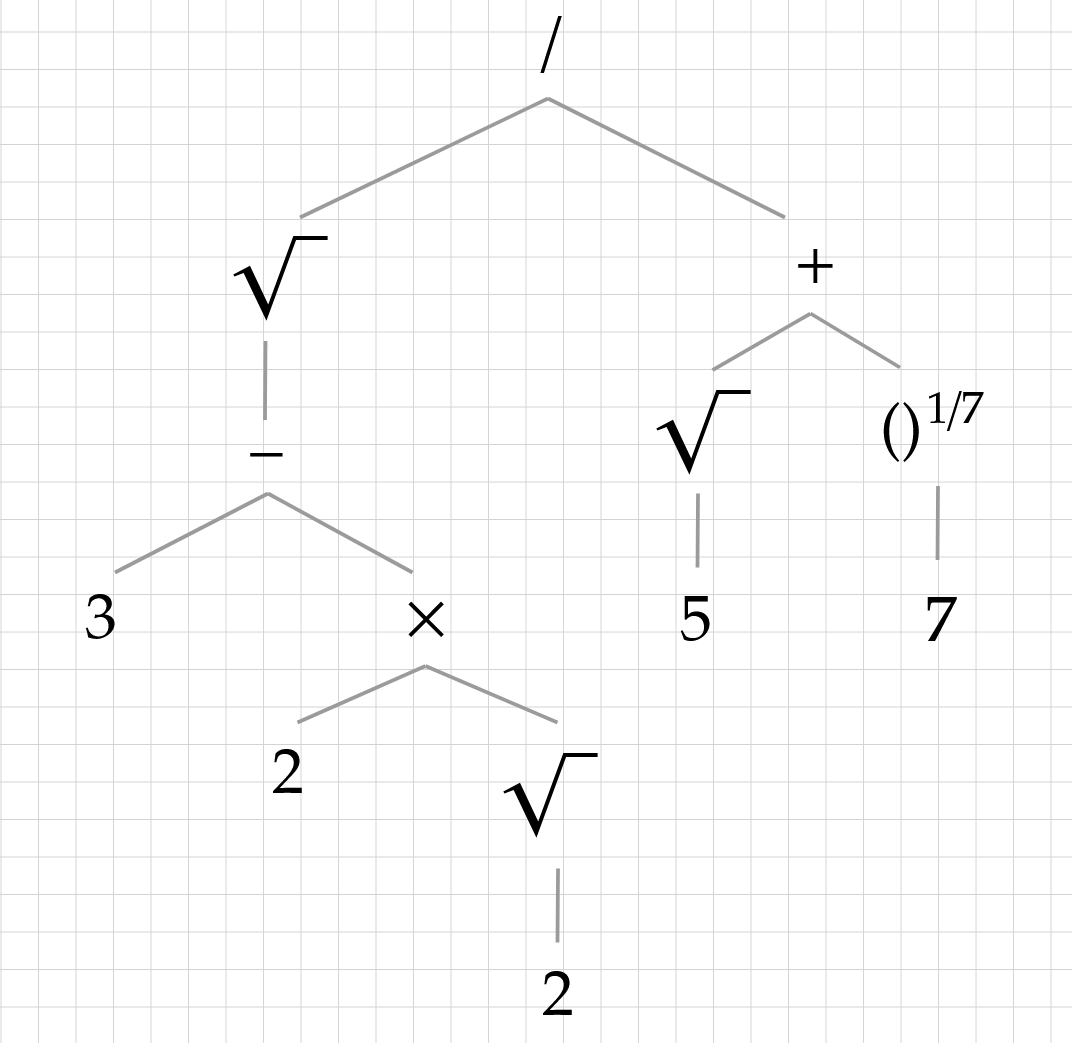

The most straightforward (and perhaps intuitive) way to represent radical-like numbers is via their expressions. This is how we typically write them out, using radicals, addition, multiplication and division. For example, \[ \frac{\sqrt{3-2\sqrt{2}}}{\sqrt{5}+(7)^{1/7}} \] is an expression that we might write out to denote a certain number. There are internal representations of expressions on computers that suffice for this kind of thing, notably abstract syntax trees (ASTs). This might look something like this:

One problem with this is that there can be multiple expressions that describe the same number. For example, \[ \frac{\sqrt{3-2\sqrt{2}}}{\sqrt{5}+(7)^{1/7}}=\frac{\sqrt{-2\sqrt{2}+3}}{(7)^{1/7}+\sqrt{5}}=\frac{\sqrt{2}-1}{\sqrt{5}+(7)^{1/7}}\,. \] Some of these transformations are obvious, like \(3-2\sqrt{2}=-2\sqrt{2}+3\). Others are less so: \(\sqrt{3-2\sqrt{2}}=\sqrt{2}-1\). This is not an insurmountable hurdle, but it makes it quite difficult to tell whether two numbers are the same. The bigger problem, depending on the application, is that there are many algebraic numbers which cannot be written in terms of radicals (so-called "unsolvable" algebraic numbers).

Algebraics are exactly the real numbers \(\alpha\) such that \(\mathbb{Q}(\alpha)\) is a finite-dimensional field extension over \(\mathbb{Q}\). If \([\mathbb{Q}(\alpha):\mathbb{Q}]=n\) ("the dimension of the field formed by appending \(\alpha\) to \(\mathbb{Q}\) with respect to the base field \(\mathbb{Q}\)"), that means that we can represent any expression involving rationals, \(\alpha\), \(+\), \(-\), \(\times\), and \(/\) as a list of \(n\) rational vector coordinates in the basis \(\{1,\alpha,\alpha^2,\ldots,\alpha^{n-1}\}\). Any number in \(\mathbb{Q}(\sqrt[3]{5})\) can be written as \(a+b\sqrt[3]{5}+c\sqrt[3]{5}^2\), for example, where \(a,b,c\in\mathbb{Q}\). This basis comes from the necessary linear dependence of \(\{1,\alpha,\alpha^2,\ldots,\alpha^n\}\) yielding the minimal polynomial \(p\): \[ p(\alpha)=c_0+c_1\alpha+c_2\alpha^2+\ldots+c_n\alpha^n=0\,, \] together with the canonical isomorphism \[\mathbb{Q}(\alpha)\cong \mathbb{Q}[X]/(p(X)) \\ \alpha\mapsto \overline{X}\,.\] For algebraic numbers \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) with minimal polynomials \(p_\alpha\) and \(p_\beta\), their sum \(\alpha+\beta\) is in \(\mathbb{Q}(\alpha,\beta)=\mathbb{Q}(\alpha)(\beta)\), which has basis a subset of \[ \bigcup_{i,j} \{\alpha^i \beta^j\}\,. \] Using linear algebra over \(\mathbb{Q}(\alpha,\beta)\) (essentially using \(p_\alpha(\alpha)=0\) and \(p_\beta(\beta)=0\)), we can determine a linear dependence of the set \[ \left\{ \alpha+\beta,(\alpha+\beta)^2,(\alpha+\beta)^3,\ldots \right\}\,, \] which is the minimal polynomial of \(\alpha+\beta\).

All this seems is simultaneously extremely opaque to the uninitiated and all too obvious to those familiar with Galois theory or field extensions. The upshot is that we can find the minimal polynomial of \(\alpha+\beta\) given only the minimal polynomials \(p_\alpha\) and \(p_\beta\) for \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), respectively, using linear algebra over rational vector spaces. Turns out you can compute the minimal polynomial for \(\alpha\beta\) too. So we can represent algebraic numbers via their exact minimal polynomials, which requires only an exact integer or rational representation. While a minimal polynomial isn't quite enough to generate a floating point approximation of an algebraic number (one needs an isolating interval, for example, to specify which root), this gives you a decent idea of the complexity that can go into number representations.

Number Representations for Boolean Operations

Doing linear algebra over non-standard fields is not a speedy process. Generally, the more numbers you seek to represent, the slower basic operations like addition and multiplication become. While not a universal rule, this is basically because larger number systems (like algebraics) depend on smaller number systems (like rationals). Our strategy, then, is to represent the absolute bare minimum set of numbers that we need to do boolean operations on triangle meshes.

The answer is, well, that we only need rational arithmetic and to represent arbitrary numbers in \(\mathbb{Q}\) (the rationals). Why? The only thing I can tell you is that I've done it before, and it turns out that wherever you'd ordinarily use a square root, atan2, sine, etc., there are tricks to avoid them. Ultimately it makes sense, as boolean operations on triangle meshes are somehow linear things, but we'll get more into that later.

Rational numbers are implemented as the Field of Fractions over the integers. That is, every rational is a numerator and a non-zero denominator having no common factors, each represented as an exact integer. Thus rationals are dependent on arbitrary precision integers, which we will cover before rationals.

Arbitrary Precision Integers

There are many arbitrary precision integer libraries out there, e.g., GMP or BigInteger. These are sufficient for our needs (in fact, I used BigInteger in my previous Java implementation). However, there are optimizations that can be done utilizing the particulars of the boolean operations algorithm. In particular, a substantial proportion of exact operations involve multiplication and addition of 32-bit floating point numbers. For example, a side-of-plane test involves adding a number of three-products \(a\times b\times c\) of these floats. We should utilize double-precision hardware multiplication where possible. In many cases, we can track the required precision exactly and avoid over-allocating memory. Finally, we know that no computation will exceed the precision thresholds to qualify for extra-fancy arithmetic algorithms like Toom-Cook multiplication bigger than Toom-2 or anything involving FFTs, so we can simplify things a bit.

Representation Overview

Our goal is to efficiently represent integers in the range \[[-2^{2^{30}}, 2^{2^{30}}]\,. \] This is not arbitrarily large; your computer likely has enough memory to store integers far greater than this. But actually representing uniformly-sampled integers of magnitude \(2^{2^{30}}\) takes upwards of 130 megabytes of space. We'd have to multiply about 17 million 64-bit integers together before reaching the limits here. If we end up dealing with numbers this large, there's little hope that our boolean operations algorithm will be competitive. Nonetheless, we'll have to keep in the back of our minds our magnitude limits.

Conveniently, most of us already think of integers in a way that doesn't inherently impose size caps. We don't allocate sections of memory to numbers like computers do. Instead, we think in digits. \[23\,567\,812\,110\] You've probably never explicitly considered the number above. Certainly you've never memorized a multiplication or division table for 23,567,812,110. Yet you have no problem gauging its relative size and some of its properties. You'd even be able to add, subtract, multiply and divide with this number effectively, though perhaps it might take some effort. The reason we can do this is that we have no problem conceptualizing arbitrarily large strings of digits — at least in theory — and we have grade-school algorithms for basic arithmetic operators (\(+\), \(-\), \(\times\), \(/\)) that extend memorized tables to bigger numbers.

We have a concept of carrying digits as it applies to addition, for example. If we want to find \(42 + 39\), we'd find ourselves only needing to compute \(2+9\) (carrying the one) and \(4+3+(1)\). Similarly, we can subtract via borrowing, multiply via pairwise digit multiplication, carrying, and addition, and divide via long division. Never do we need to memorize anything beyond single-digit operations, like \(8\times 4=32\) or \(72/8=9\).

This is exactly what we'll accomplish using a computer. On occasion we'll use fancier algorithms than the ones we learned in grade school, but the main difference will be the level of "memorization" that computers can achieve. While we can only reasonably handle single-digit operation tables, computers can "look-up" any addition, multiplication, division or subtraction that fits in a 64-bit integer using hardware. The result is that whereas we think in base ten digits (zero through nine), our arbitrary integer program will use base \(2^{64}\). It's worth spending a few minutes thinking about the implications of such a massive increase in base. The number with digit string \(ab\) is equal to \(a\cdot 2^{64} + b\), with \(a\) and \(b\) consisting of 64-bit integers in the range \([0,2^{64}-1]\). Because each "digit" in base \(2^{64}\) consists of 64 binary digits, folks typically call \(a\) and \(b\) "words" or "limbs," leaving "digit" to describe only the binary constituents. "Word," in this case, is appropriate since 64 bits is a common machine word size. \[ \underbrace{110\ldots 0}_{k^\text{th}\text{ word}} \quad \underbrace{010\ldots 1}_{(k-1)^\text{th}\text{ word}} \quad \ldots \quad \underbrace{101 \ldots 1}_{0^\text{th}\text{ word}}\,^{\leftarrow \,0^\text{th}\text{ digit of }0^\text{th}\text{ word}} \]

Our strategy will be to maintain a list "words" \([w_k, w_{k-1}, \ldots, w_1, w_0]\) together with a sign value \(s\in \{-1,0,1\}\), representing the target integer \[ s\sum_{i=0}^k w_i\cdot 2^{64i}\,. \]

A handy fact about writing numbers in base \(2^{64}\), is that a number \(z\) with words \([w_k,w_{k-1},\ldots,w_0]\) has binary representation equal to the binary representations of \(w_k, w_{k-1}, \ldots, w_0\) appended together. This strategy of viewing numbers in base \(2^n\) as actually in base \(2\) is somewhat ubiquitous in hexadecimal or octal numbers. Writing each word \(w_i\) in binary as \(w_i=\sum_{j=0}^{64} b_{i,j}2^j\), we can see why this is: \[\sum_{i=0}^k w_i2^{64i}=\sum_{i=0}^k \sum_{j=0}^{64}b_{i,j}2^{64i+j}=\sum_{m=0}^{64k-1}b_{\lfloor m/64\rfloor,m\bmod64}2^m\,.\] Alternatively, we can see this via the ring isomorphism \[ \begin{align*} \mathbb{Z}[x]/(2^{64}-x)&\cong \mathbb{Z}[x]/(2-x) \\ x&\rightarrow x^{64} \\ 2&\leftarrow x \end{align*}\,. \] Of course, this is only really illuminating if you understand what ideal representatives in \(\mathbb{Z}[x]/(2-x)\) can look like, which is basically what we're trying to show in the first place. Anyway, as is sometimes the case for algebra, the more one tries to explain things the more confusing it appears, so we'll leave it at that.

Representation Details

Each word will be a 64-bit, unsigned integer (uint64_t in C++).

In order to maintain the ability to efficiently process both small, stack-allocated exact integers and large, heap-allocated exact integers, we hold words in a fixed-size array base_value with overflow in an extensible std::vector list data structure.

When we know beforehand the maximum precision necessary, we can save memory and compute cycles by manually setting the size of base_value and omitting the list data structure extended_value altogether:

template<int base_allocation = 0, bool extensible = true>

class integer ... {}

...

// The sum of arbitrary numbers of integer may require many

// words to represent.

exact::integer<> a(0, 0); // a = 0

for(const exact::integer<> b : to_sum){

a.add_local(b);

}

// The product of two 1-word integers fits in a 2-word integer.

exact::integer<2, false> c(15, 0); // c = 15

exact::integer<2, false> d(1, 63); // d = 2^63

exact::integer<2, false> e = c.multiply(d);

We maintain the number of words comprising the exact integer in an int32_t member word_count.

The precision of word_count is the only limiting factor to the maximum representable integer; should the need arise, simply changing the type to int64_t would dramatically increase the capacity.

Though as mentioned previously, there is little chance that this would be necessary.

In addition to a straightforward int signum flag, we implement a well-known strategy of keeping a separate order-of-magnitude int32_t value shift in addition to the word array.

This is very much akin to scientific notation, where we save quite a bit of ink writing \(1\,230\,000\,000\) as \(1.23\cdot 10^{9}\).

But since we're working in base \(2^{64}\), shift encodes how many powers of \(2^{64}\) to multiply the word string by.

More formally, a sign value \(s\), words \([w_k, w_{k-1}, \ldots, w_0]\) and non-negative shift \(p\) represents the exact integer

\[s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i\cdot 2^{64i}\,.\]

This is also entirely analogous to the binary left-shift operator <<; viewed as individual base-64 digits this is

\[s\cdot (w_kw_{k-1}\ldots w_0 << p)\,. \]

With the introduction of shift, we introduce ambiguity in our representation.

The number \([s,w_1,w_0,p]=[1,12,0,0]\) is equal to \([s,w_1,w_0,p]=[1,0,12,1]\).

To remove this ambiguity, and improve performance of shift-independent operations (like multiplication), we maintain the "maximal shift property."

Of all representations \(R_1,R_2,\ldots,R_q\) for some non-zero integer \(z\), there is exactly one with maximal shift value.

This one is canonical, and to keep all exact integers in canonical representation, all we have to do is remove trailing zero words and update shift accordingly.

C++ exact integer header file snippet

#ifndef INTEGER_HPP

#define INTEGER_HPP

#include <stdint.h>

#include <array>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

namespace exact {

// The existence of "extended_value" will be templated for advanced usage, by

// using one of the following structs as an inherited parent

struct extensible_int {

std::vector<uint64_t> extended_value {};

};

struct nonextensible_int {};

/**

* This is a class for representing integers in the range

* [-2^(2^30), 2^(2^30)],

* that is, very large but not arbitrarily-large integers.

*

* The template value "base_size" indicates the capacity (in words) of the fixed-size array base_value,

* with any overflow spilling over into extended_value.

*

* The template value "extensible" indicates whether extended_value will be available for use.

* If extensible is set to false, any overflow or carry from base_value will result in undefined behavior,

* but you'll save 24 bytes of memory use per exact integer instance.

*

* Integers will be represented internally by a bitstring split up into uint64_t chunks, contained

* in base_value and extended_value. This big-endian bitstring occupies 64*word_count bits in base_value and

* extended_value, in the order

* base_value[0], base_value[1], ..., base_value[base_size - 1], extended_value[0], ..., extended_value[word_count - 1].

* If word_count <= base_size, then the bitstring only occupies base_value and extended_value is empty.

*

* This class uses x86 intrinsics.

*

* @author Alan Koval

*/

template<int base_size = 0, bool extensible = true>

class integer : std::conditional_t<extensible, extensible_int, nonextensible_int> {

public:

/**

* Constructs the exact integer equal to

* value * 2^two_power

*

* two_power must be positive.

*

* This constructs an internal representation with maximal shift and minimum

* number of words

*/

integer(const int64_t value, const int32_t two_power);

/**

* Constructs the zero integer

*/

integer(): signum(0), first_bit_offset(-1), word_count(0), shift(0) {};

/**

* Returns the current (left) shift for this exact integer.

* An integer is represented internally as a bitstring b together with a shift s,

* so that the actual value, neglecting sign, is 2^(64*s) * b

*/

int32_t get_shift() const;

/**

* Returns -1 if this integer is negative, 0 if this integer is zero, 1 if this integer is positive

*/

constexpr int sign() const;

private:

/**

* signum == 1 if this number is positive,

* signum == -1 if this number is negative,

* signum == 0 if this number is zero.

*/

int32_t signum {0};

/**

* This stores the left-shift value p such that the value of this integer is

* signum * 2^(64p) * sum_i w_i 2^(64i),

* where w_i is this.word(this.word_count - 1 - i).

*

* Note that constructor uses exponents of base 2, whereas shift encodes an exponent of base 2^64.

*

* While shift must be non-negative, we use int32_t to facilitate taking differences of shift values,

* which is a common operation.

*/

int32_t shift {0};

/**

* This is the first non-zero bit in the words making up this integer.

* For example, if first_bit_offset == 76, then the first non-zero bit occurs in

* this.word(1) at binary digit 76 - 64 = 12.

*

* If this exact integer is zero, then first_bit_offset is -1.

*/

int32_t first_bit_offset {0};

/**

* This is the number of words in use by the integer.

* If extended_value is non-empty, then word_count is equal to base_size + extended_value.size().

* Otherwise, word_count <= n, and any value base_value[k] with k >= word_count means nothing.

*/

int32_t word_count {0};

/**

* One of the containers holding word values, with the other being extended_value (if extensible == true).

* Please note that base_value (possibly extended by extended_value) is in *big-endian* order.

* The most significant word is base_value[0].

*/

std::array<uint64_t, base_size> base_value{};

/**

* Obtains a reference to the (index)th word of this representation.

* index must be non-negative and less than word_count. No bounds checking is performed.

*/

uint64_t& word(const int32_t index);

/**

* The read-only version of word(int32_t index) above.

*/

uint64_t word_r(const int32_t index) const;

/**

* adds another entry to the word list, increases word_count by 1, returns a reference to the new word,

* which has been set to zero.

*

* NOTE: calls to push_word may invalidate existing references to words, see

* https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/vector/emplace_back

*/

uint64_t& push_word();

/**

* deletes the last word, decreases word_count by 1. Does nothing if word_count is already 0

*

* NOTE: calls to push_word may invalidate existing references to words, see

* https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/container/vector/emplace_back

*/

void pop_word();

};

}

#endifImplementation Details

Now that we have a solid internal representation for large integers, we can implement the various operations we expect to use on integers. This includes addition, subtraction, multiplication, and integer division. We build these up using a number of smaller operations, including negation, left shift, right shift, comparison, and bit-wise AND. Looking forward to its use in exact rational arithmetic, we'll also need the greatest common divisor (GCD) and least common multiple (LCM) of two large integers.

For each operation, we'll verify that first_bit_offset and signum are correctly set, and that shift is maximal.

The only other exact::integer members, base_value, extended_value, and word_count, are maintained by the functions push_word, pop_word and the reference retrieval function word.

All changes to the number of words are made through these push and pop functions, so we don't need to explicitly track word_count through the other operations.

Negation

Since the sign of the integer is equal to the member signum, we need only make the transformation

\[ \begin{align*}

(\text{signum}=1)&\to (\text{signum}=-1) \\

(\text{signum}=0)&\to (\text{signum}=0) \\

(\text{signum}=-1)&\to (\text{signum}=1)

\end{align*}\,, \]

that is,

/**

* Mutates the integer instance by multiplying by -1.

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::negate_local(){

this->signum *= -1;

return *this;

}first_bit_offset remains correct and shift remains maximal.

Left shift

As with the binary case, left shift is multiplication by a power of two. In a "pure" sense, left shift in base \(2^{64}\) ought to be multiplication by some integer \(2^{64k}\), so that we shift words to the left, as we do with digits in binary. However, it is sometimes convenient to allow multiplication by other powers of two.

/**

* Mutates the integer instance by multiplying by 2^(64 * shift_bulk + shift_excess)

*

* shift_bulk and shift_excess must be non-negative, with shift_excess not exceeding 63.

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::shift_l_local(const int32_t shift_bulk, const int32_t shift_excess){

// left shift, as opposed to right shift, will never change signum

this->shift += shift_bulk;

if(shift_excess == 0){

return *this;

}

// do smaller word bit-shifts

const int32_t shift_excess_inv = 64 - shift_excess;

if(this->first_bit_offset >= shift_excess){

// we have enough zeros in the first word to shift left as much as needed

for(int32_t i = 0; i < this->word_count; ++i){

uint64_t& a = this->word(i);

const uint64_t b = ( i == this->word_count - 1 ? 0u : this->word(i + 1) );

a = (a << shift_excess) | (b >> shift_excess_inv);

}

} else {

// we don't have enough space to shift left; instead we add another word to the

// end and shift *right* by (64 - shift_excess)

this->push_word();

for(int32_t i = 0; i < this->word_count; ++i){

const int32_t j = this->word_count - i - 1;

uint64_t& a = this->word(j);

const uint64_t b = ( j == 0 ? 0u : this->word(j - 1) );

a = (a >> shift_excess_inv) | (b << shift_excess);

}

}

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

this->recompute_first_bit_offset();

return *this;

}

We first consider the case where shift_excess == 0.

In this case, we add shift_bulk to this->shift and return.

Given signum \(s\), shift \(p\) and words \([w_k,w_{k-1},\ldots,w_0]\), we indeed have

\[2^{64\cdot\text{shift_bulk}} \cdot s\cdot 2^{64p}\sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}=

s \cdot 2^{64(p+\text{shift_bulk})}\cdot \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}\,,\]

so the resulting representation is of the integer we want.

Since multiplication by a positive integer can't change the sign, signum remains correct.

Since the words \([w_k,\ldots,w_0]\) remains the same, first_bit_offset also remains correct.

Finally, since \(s 2^{64p}\sum_i w_i 2^{64i}\) is a maximal-shift representation, \(2^{64}\) does not divide \(\sum_i w_i 2^{64i}\).

This means that \(s 2^{64(p+\text{shift_bulk})} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i} \) is also a maximal-shift representation.

If shift_excess is not zero, then we know that signum, first_bit_offset, and shift make up a valid, maximal-shift representation after this.shift is incremented by shift_bulk.

Since this->remove_trailing_zero_words() conforms the integer to the maximal-shift property and this->recompute_first_bit_offset(), well, recomputes first_bit_offset, we need only confirm that the intermediate lines transform the integer into a representation with value multiplied by \(2^{\text{shift_excess}}\).

Let \(\alpha=\text{shift_excess}\) be less than 64, and observe that

\[

\begin{align*}

2^{\alpha}\cdot s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i} &= s \cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k 2^\alpha w_i 2^{64i} \\

&= s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k 2^\alpha\left((w_i \bmod 2^{64-\alpha}) + 2^{64-\alpha}\lfloor w_i/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor\right) 2^{64i} \\

&= s\cdot 2^{64p}\sum_{i=0}^k \left( 2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha})2^{64i}+2^{64(i+1)}\lfloor w_i/2^{64-\alpha}\rfloor \right) \\

&= s\cdot 2^{64p}\left(

2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha}) +

2^{64(k+1)}\lfloor w_k/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor + \right.\\

&\left. \qquad\qquad\qquad \sum_{i=1}^k 2^{64i}\left( 2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha})+\lfloor w_{i-1}/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor \right)

\right)

\end{align*}

\]

If we set \(w_{-1}=0\), this simplifies slightly to

\[

s\cdot 2^{64p}\left(

2^{64(k+1)}\lfloor w_k/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor +

\sum_{i=0}^k 2^{64i}\left( 2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha})+\lfloor w_{i-1}/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor \right)\right)\,.

\]

Now \(2^\alpha (w_i \bmod 2^{64-\alpha})\) is the lower \(64-\alpha\) bits of \(w_i\) shifted \(\alpha\) left, and \(\lfloor w_{i-1}/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor\) is the upper \(\alpha\) bits of \(w_{i-1}\) shifted \(64-\alpha\) right.

The sum \( 2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha})+\lfloor w_{i-1}/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor \) has no overlapping bits and can be computed via binary bit-wise OR:

\[ 2^\alpha(w_i\bmod 2^{64-\alpha})+\lfloor w_{i-1}/2^{64-\alpha} \rfloor=(w_i << \alpha)\,|\,(w_{i-1}>>(64-\alpha))\,. \]

In short, we have

\[ 2^{\alpha}\cdot s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}= s\cdot 2^{64p}\left( 2^{64(k+1)}(w_k >> (64-\alpha))+ \sum_{i=0}^k (w_i << \alpha)\,|\,(w_{i-1}>>(64-\alpha)) 2^{64i} \right)\,. \]

This is just a formal way of saying "treat \([w_k,\ldots,w_0]\) as a single sequence of binary digits, add \(\alpha\) zeros to the end, and reform into words." Below is an example with three words and \(\alpha=4\). \[ \begin{align*} &\color{red}{01101\ldots 01001} \quad \color{purple}{11011\ldots 00010} \quad \color{green}{10100\ldots10010} \\ \color{red}{0110\quad}&\color{red}{1\ldots01001}\color{purple}{1101}\quad\underbrace{\color{purple}{1\ldots00010}}_{64-\alpha}\underbrace{\color{green}{1010}}_{\alpha}\quad\color{green}{0\ldots 10010}\color{grey}{0000} \end{align*} \]

Anyway, if shift_excess (\(\alpha\)) is less than or equal to first_bit_offset, then the term

\[2^{64(k+1)}(w_k >> (64-\alpha))\]

is zero (the leading red "0110" in our example).

This means we do not need to add a new word, and we can overwrite each word \(w_i\) with

\[ (w_i << \alpha)\,|\,(w_{i-1}>>(64-\alpha))\,, \]

which our function clearly does in this case.

(Note that this->word(i) returns the word \(w_{k-1-i}\) since it counts from the beginning of the word list.)

If shift_excess \(\alpha\) is greater than first_bit_offset, then the term \(2^{64(k+1)}(w_k >> (64-\alpha))\) is not zero.

We then add a word to the end of the list via this->push_word() (which becomes the new \(w_0\)).

This has the effect of multiplying by \(2^{64}\).

We then must perform a right shift of \(64-\alpha\), which results in a similar bit-shifting procedure as before.

I'll leave the details for the interested reader.

Right shift

As with binary, a right shift is an integer division by a power of two, i.e.,

\[z>>j=\begin{cases}

\lfloor z/2^j \rfloor &\text{if }z \geq 0 \\

\lceil z/2^j \rceil &\text{if }z < 0

\end{cases}\,.\]

In a "pure" sense, right shift in base \(2^{64}\) ought to be integer division by some \(2^{64i}\), but we find it convenient to allow any integer (non-negative) power of two.

Right shift differs from left shift in a few notable ways.

First, a right shift operation may change the signum of a number, if the result is zero.

Secondly, a right shift more substantially interacts with this->shift, since shift must remain non-negative.

Here's the algorithm:

/**

* Mutates the number to be

* this / 2^(64 shift_bulk + shift_excess),

* rounded toward zero.

*

* shift_bulk must be non-negative.

* shift_excess must be non-negative and less than 64.

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::shift_r_local(int32_t shift_bulk, const int32_t shift_excess){

// shift by multiples of 64 first, since that doesn't involve bit-shifting uint64_t entries

if(this->shift >= shift_bulk){

// A value of shift is a multiplier 2^(64 shift) of the integer; dividing by 2^(64 shift_bulk)

// is just decreasing shift -- as long as the resulting value of shift is non-negative!

this->shift -= shift_bulk;

} else {

// In this case, this->shift - shift_bulk is negative.

// We set this->shift to zero and pop off (shift_bulk - this->shift) of the least-significant words.

shift_bulk -= this->shift;

this->shift = 0;

while(shift_bulk > 0 && this->word_count > 0){

this->pop_word();

--shift_bulk;

}

}

// right shift can pop 1's off the end of a number resulting in a long string of zeros

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

// if we've either ran out of digits or completed our shift, return

if(shift_excess == 0 || this->signum == 0){

// if we pop off all the digits we may be left with zero, otherwise first_bit_offset will be the same

if(this->signum == 0){

this->first_bit_offset = -1;

}

return *this;

}

if(this->shift > 0){

// Add another word to the end so right shift doesn't needlessly chop off digits.

// Since shift_excess < 64, a single word is sufficient.

this->push_word();

--this->shift;

}

// Compute excess right-shift.

const int32_t shift_excess_inv = 64 - shift_excess;

for(int32_t j = this->word_count - 1; j >= 0; --j){

uint64_t& a = this->word(j);

const uint64_t b = ( j == 0 ? 0 : this->word(j - 1) );

a = (a >> shift_excess) | (b << shift_excess_inv);

}

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

this->recompute_first_bit_offset();

return *this;

}

For a number with signum \(s\), shift \(p\) and words \([w_k,w_{k-1}, \ldots, w_0]\), the easiest case when dividing by \(2^{64\alpha}\) is when \(p\geq \alpha\).

In this case, the division is exact and yields

\[

2^{-64\alpha} \cdot s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i} = s \cdot 2^{64(p-\alpha)} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}\,.

\]

That is, we subtract shift_bulk from this->shift and we're done.

If \(p<\alpha\), then we have to distribute some of the \(2^{-64\alpha}\) term to the words:

\[

\begin{align*}

2^{-64\alpha} \cdot s\cdot 2^{64p} \sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}&=s\cdot 2^{-64(\alpha-p)}\sum_{i=0}^k w_i2^{64i} \\

&=s\sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64(i+p-\alpha)} \\

&=s\left( \sum_{i=\alpha-p}^{k}w_i2^{64(i+p-\alpha)}+\underbrace{\sum_{i=0}^{\alpha-p-1}w_i2^{64(i+p-\alpha)}}_{<1\text{ since }w_i<2^{64}} \right)

\end{align*}

\]

The second sum is less than one by geometric series, and is stripped by an integer division (since \(|s|\leq 1\)).

Since removing words via this->pop_word() shifts indexes so that \(w_i\) becomes \(w_{i-1}\), all we have to do is call this->pop_word() \(\alpha-p\) times.

Since we've possibly removed words, there may be trailing zeros, violating the maximal shift property.

this->remove_trailing_zero_words() removes these and modifies signum to zero if necessary.

If shift_excess is zero or signum is zero, then (1) signum is correct because of this->remove_trailing_zero_words() (note that signum can't flip from 1 to -1 or vice versa) and (2) shift is maximal for the same reason.

If signum is not zero, then the first bit from the left has remained the same (this->pop_word() removes words from the right), so first_bit_offset is still correct.

Otherwise, there is no first bit and we set first_bit_offset to -1.

We can then return.

If we have remaining shift left (shift_excess is not zero), we have to apply bit-wise operations to individual words.

It's worth noting at this point that \(\lfloor x/(ab) \rfloor=\lfloor \lfloor x/a \rfloor/b \rfloor \) for positive \(x\), \(a\), and \(b\), which justifies first dividing by the bulk shift, then by the excess shift.

Writing \(x=aq+r\) and \(q=bq'+r'\) with \(0\leq r \leq a-1\) and \(0\leq r' \leq b-1\), we have

\[ \lfloor \lfloor x/a \rfloor/b \rfloor = q'\,. \]

But

\[ \begin{align*}

x&=a(bq'+r')+r \\

&= abq' +(ar' + r)

\end{align*}\]

with \(ar'+r\leq a(b-1)+a-1=ab-1\), so \(\lfloor x/(ab) \rfloor=q'\) as well.

The excess right shift bit shifting is done by a very similar process to the excess left shift in the previous section; I will leave the details as an exercise.

Since we call this->remove_trailing_zero_words() and this->recompute_first_bit_offset(), the maximal shift property is maintained, signum is set to zero if necessary, and first_bit_offset is correctly set.

Comparison

Given two exact integers \(a\) and \(b\), we'd like to determine whether \(a=b\), \(a< b\), or \(a>b\). We know how to do this for base 10 numbers. First check whether one number has more digits than the other. If not, go digit by digit from most significant to least significant, comparing between the numbers. The number with the first smaller number is less in absolute value. If all the digits match, the numbers are equal. The process also works in base \(2^{64}\). Supposing \(a\) and \(b\) are positive, the number of words in \(a\) and \(b\) is

const int32_t words_a = a.shift + a.word_count - a.first_bit_offset / 64;

const int32_t words_b = b.shift + b.word_count - b.first_bit_offset / 64;shift term accounts for trailing words not included in the word list, and the integer division first_bit_offset / 64 accounts for leading zero words in the word list.

Certainly if \(a\) has a more significant word than \(b\), then \(a\) is greater than \(b\) because a single \(2^{64k}\) term is greater than the maximum value \(\sum_{i=0}^{k-1} (2^{64}-1) 2^{64i}\) from all smaller terms, by geometric series.

But we can actually do a bit better. Recall that the binary representations for \(a\) and \(b\) are easily accessible from the binary representations from the words making up \(a\) and \(b\). We can compare the place of the most significant binary digit of \(a\) to the most significant binary digit of \(b\). The most significant bits \(a\) and \(b\) are

const int64_t bits_a = 64 * (a.shift + a.word_count) - a.first_bit_offset;

const int64_t bits_b = 64 * (b.shift + b.word_count) - b.first_bit_offset;If the most significant bit of \(a\) matches that of \(b\), then we can compare \(a\) to \(b\) word by word from most significant to least significant. As we move to the less significant words, we can imagine that we subtract off the higher words from both \(a\) and \(b\), and that the current word comparison is the most significant. Thus we can make the same geometric series argument for the correctness of our comparison conclusion.

This algorithm is implemented below:

/**

* Compares the absolute value of this to the absolute value of other.

* Returns std::strong_ordering::greater if |this| > |other|,

* std::strong_ordering::less if |this| < |other|, and

* std::strong_ordering::equivalent if |this| == |other|

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

std::strong_ordering exact::integer<n, ext>::abs_cmp(const exact::integer<n, ext>& other) const {

const std::strong_ordering cmp = this->get_max_bit() <=> other.get_max_bit();

if(cmp != std::strong_ordering::equivalent){

return cmp;

}

// Special case for zeros. We know that this->get_max_bit() == other.get_max_bit() here,

// so if one of the numbers is zero, they both are.

if(this->signum == 0){

return std::strong_ordering::equivalent;

}

// Start comparing bits. Since we know that the two integers share a max bit,

// we don't need to account for shift; just start at the first words with a non-zero digit in each

int32_t i = this->first_bit_offset / 64;

int32_t j = other.first_bit_offset / 64;

while(i < this->word_count || j < other.word_count){

const std::strong_ordering res = (i < this->word_count ? this->word_r(i) : 0u) <=> (j < other.word_count ? other.word_r(j) : 0u);

if(res != std::strong_ordering::equivalent){

return res;

}

++i;

++j;

}

return std::strong_ordering::equivalent;

}Accounting for sign is similarly straightforward. If a number is negative and the other positive, the positive one is bigger. If both numbers are negative, the smaller one in absolute value is bigger. Getting the logic tests as short as possible while accounting for zero is perhaps not as easy as one might hope for, but manageable:

/**

* The C++ spaceship operator <=> applied to integers returns:

* std::strong_ordering::less if a < b

* std::strong_ordering::greater if a > b

* std::strong_ordering::equivalent if a = b

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

constexpr auto exact::operator<=>(const exact::integer<n, ext>& a, const exact::integer<n, ext>& b) {

const std::strong_ordering cmp_v = a.abs_cmp(b);

// If a == b, then signum(a) == signum(b) and |a| == |b|.

// Conversely, if |a| == |b|, then a = +/- b.

// If signum(a) = signum(b) = 0, then a = b = 0.

// If signum(a) = signum(b) = 1, then a and b are positive so that a = b.

// If signum(a) = signum(b) = -1, then a and b are negative so that a = b.

if(a.signum == b.signum && cmp_v == std::strong_ordering::equivalent){

return std::strong_ordering::equal;

}

const int cmp = cmp_v == std::strong_ordering::less ? -1 : 1;

// If signum(a) < signum(b), then a must be less than b. If signum(a) == signum(b) and

// a != b (from above), then either:

// signum(a) = signum(b) = 1, in which case a < b iff cmp == -1

// signum(a) = signum(b) = -1, in which case a < b iff cmp == 1

// Conversely, suppose that a != b and a < b. If signum(a) is not less than signum(b), it must

// be that signum(a) = signum(b). If signum(a) = signum(b) = 1, then cmp == -1 since a < b ==> |a| < |b|.

// If signum(a) = signum(b) = -1, then cmp == 1 since a < b ==> |a| > |b|. In either case,

// signum(a) != cmp.

if(a.signum < b.signum || a.signum == b.signum && a.signum != cmp){

return std::strong_ordering::less;

}

return std::strong_ordering::greater;

}Bit-wise AND

Since an integer \(a\) written in base \(2^{64}\) has easily accessible binary representation (append the binary representations of its constituent words together), we can extend a binary bit-wise AND operator to arbitrary integers.

It's worth noting that some binary operators — like NOT, NOR and XNOR — only work on integers with bounded precision.

Since there are infinitely many leading zeros to every arbitrary-precision integer, any operator that can turn zeros into ones will result in infinitely many leading ones.

This is of course not an integer (but can be considered a p-adic number).

In the case of AND, however, 0 & 0 = 0 so we need not worry.

We'll implement a bit_and_local(other) function, which overwrites an existing integer this with this & other.

The convenient fact about AND is that we only have to consider bits in other that lie within occupied words in this.

For example, if this consists of four words with shift 3, but other consists of 100 words with shift 2, we only need to access words \(w_1,w_2,w_3\) and \(w_4\) since only those words contain bits overlapping with the bits of this.

Other than lining up the words according to their significance, the implementation is a very straight-forward word-wise uint64_t AND operation:

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::bit_and_local(const exact::integer<n, ext>& other){

// we want a map g:\mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N} so that the word

// other.word(n)

// shares the same (absolute) bits with

// this.word(g(n))

//

// Given maps p and q which map this words and other words to absolute words:

// p(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - n) + this.shift

// q(n) = (other.word_count - 1 - n) + other.shift,

// we have g = p^-1 \circ q.

// p^-1(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - n) + this.shift

// so that

// g(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - ((other.word_count - 1 - n) + other.shift)) + this.shift

// = n + (this.word_count - other.word_count) + (this.shift - other.shift)

const int32_t g0 = (this->word_count - other.word_count) + (this->shift - other.shift);

const int32_t gn = g0 + other.word_count;

for(int32_t i = 0; i < this->word_count; ++i){

this->word(i) &= ( i >= g0 && i < gn ? other.word_r(i - g0) : 0u );

}

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

this->recompute_first_bit_offset();

return *this;

}

Since this->remove_trailing_zero_words() and this->recompute_first_bit_offset() are called at the end, signum and first_bit_offset are set correctly (a bit-wise AND cannot flip the sign), and the maximal shift property is preserved.

Addition and subtraction

Let's first consider the case of adding two positive numbers together. If we were to use pencil and paper, we'd first line up the numbers, one above the other so that aligned digits have the same significance, filling in any leading zeros so the two numbers are the same length. We'd then proceed right to left, summing aligned digits. If the sum is less than 10, we write the sum in the space below the aligned digits. If the sum is greater than 10, we "carry" the one — meaning add an extra one to the sum immediately to the left — and write the sum minus 10 (a single digit) in the space below the aligned digits. If there is a carry on the last sum, we append a one to the left of the result. \[ \begin{array}{rl} {\scriptsize 1}\,{\scriptsize 1}\,\,\,\,\,\, \\ 005671 \\ +\,\,100832 \\ \hline 106503 \end{array} \] In the example above, we carry twice, in the sum \(7+3=10\) and in the sum \(1+6+8=15\).

Each digit sum is the grouping of like power-of-ten terms, with carrying "spilling" into the next higher power-of-ten. In base \(b\), two numbers have expansion \[ \begin{align*} x=\sum_{i=0}^p x_i b^i \\ y=\sum_{i=0}^q y_i b^i \end{align*} \] and sum, assuming that \(x_i=0\) when \(i>p\) and \(y_i=0\) when \(i>q\), \[ x+y = \sum_{i=0}^{\max(p,q)} b^i(x_i + y_i)\,. \] If \(x_i+y_i\geq b\), then \(x_i+y_i=b+(x_i+y_i-b)\) and the \(b^i \cdot b=b^{i+1}\) term "carries" to the next term, leaving \(0\leq x_i+y_i-b< b\).

If we seek to mutate a base \(2^{64}\) number \(x\) by adding another base \(2^{64}\) number \(y\) to it, we can ask which words in \(x\) will have to change. Certainly, any word in \(x\) with less significance than the least (nonzero) significant word in \(y\) will be left untouched, since adding zero does nothing, and there can be no carry from adding zero. Any word with significance matching the significance in \(y\) will most likely change, unless the corresponding word in \(y\) is zero or equal to \(2^{64}-1\) with a carry. Words in \(x\) with significance much greater than the most significant word in \(y\) will almost surely not change, unless a carry propagates through every prior word in \(x\) down to the significance of the most significant word in \(y\). This scenario requires every word \(x_i\) down to the most significant word in \(y\) to be equal to \(2^{64}-1\). \[ \begin{array}{rl} 0000004563200000 \\ +\,\,4593995968382990 \\ \hline \color{gray}{459}\color{orange}{400}\color{red}{05315}\color{gray}{82990} \end{array} \] A base 10 example is shown above, with \(y\) above and \(x\) below. Digits in gray didn't change from \(x\), digits in red changed and were very likely to change, and digits in orange changed because of a propagated carry. Note that all but the first orange digit must have a nine above it.

Our algorithm starts at the least significant non-zero word in \(y\), and moves left, keeping a carry flag as it goes. Once it reaches the end of significant words of \(y\), it continues left contingent on a propagated carry.

/**

* Modifies "this" integer to be this + other.

*

* this.signum be be equal to other.signum.

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::add_local_matches_signum(const exact::integer<n, ext>& other){

// map the words of other onto the words of this, then extend this to include

// the words of other, then perform addition word-wise from least significant bit

// to most significant bit

// we want a map g:\mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N} so that the word

// other.word(n)

// has the same significance as

// this.word(g(n))

//

// Given maps p and q which map this words and other words to significance values:

// p(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - n) + this.shift

// q(n) = (other.word_count - 1 - n) + other.shift,

// we have g = p^-1 \circ q.

// p^-1(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - n) + this.shift

// so that

// g(n) = (this.word_count - 1 - ((other.word_count - 1 - n) + other.shift)) + this.shift

// = n + (this.word_count - other.word_count) + (this.shift - other.shift)

// = n + g0

// Note that

// g^-1(n) = n - g(0)

// expand_to_subsume adds words (to the right and to the left) so that there is a word

// of equal significance in this for every word in other.

// These words, formally implicitly zero in this, will very likely be modified during the addition, so

// we'd have to add them anyway.

this->expand_to_subsume(other);

const int32_t g0 = (this->word_count - other.word_count) + (this->shift - other.shift);

unsigned char carry = 0;

// j and i are indices of words in other and this (respectively) with equal significance

int32_t j = other.word_count - 1 + g0;

for(int32_t i {other.word_count - 1}; i >= 0; --i){

uint64_t& target = this->word(j);

carry = _addcarry_u64(carry, other.word_r(i), target, &target);

--j;

}

if(carry != 0){

// propagate the carry until carry is zero, or we run out of digits

while(j >= 0 && carry != 0){

uint64_t& target = this->word(j);

carry = _addcarry_u64(carry, 0u, target, &target);

--j;

}

// if we ran out of digits, we need to add another one

if(j < 0 && carry != 0) {

// push word, right shift by 1 word, set left-most word to 1u

this->push_word();

for(int32_t j {this->word_count - 1}; j > 0; --j){

this->word(j) = this->word_r(j-1);

}

this->word(0) = 1u;

}

}

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

this->recompute_first_bit_offset();

return *this;

}

Addition can lead to the least significant words becoming zero.

In base 10, \(13499+1=13500\) for example.

Addition can also lead to a decrease in first_bit_offset, if a carry occurs or \(y\) has more significant words than \(x\).

Calling remove_trailing_zero_words() and recompute_first_bit_offset() maintains the maximal shift property and resets first_bit_offset.

Since the addition of two positive numbers results in a positive number, and the addition of two negative numbers results in a negative number, the signum need not be changed.

Now a more interesting question is the case of subtraction, the case when the sign of \(y\) does not match the sign of \(x\). If one or the other is zero, it's easy; we'll have a case for that. But the grade-school subtraction algorithm is considerably more complicated; instead of carrying excess from left to right, we borrow from more significant digits to make up for deficiency in less significant digits. This is a slight problem when the more significant digit is zero. In this case, we have to borrow from an even more significant digit, turn the zero digit (and any other intermediate zero digits) to a nine, and proceed. If there are no more significant digits from which to borrow, the usual procedure is to restart the entire calculation, flipping the roles of \(x\) and \(y\), and negate the result.

This is annoying to implement correctly.

Fortunately, as you might have forseen, we can avoid this borrowing business entirely by transforming the subtraction into an addition using a slightly modified two's-complement scheme.

Suppose we are attempting to calculate \(y-x\), where \(x\) and \(y\) have matching sign.

If \(x\) has words \([w_k,w_{k-1},\ldots,w_0]\), let \(\sim x\) be the integer represented by words \([\sim w_k,\sim w_{k-1},\ldots,\sim w_0]\), where \(\sim w_i\) is the binary negation as a 64-bit unsigned integer.

This is a representation-dependent operation, since appending a zero word \(w_{k+1}\) doesn't change the value of \(x\) but does change \(\sim x\).

Suppose for now that shift is zero for both \(x\) and \(y\).

Observe that

\[

\begin{align*}

\sim x=\,\,\sim\sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}&=\sum_{i=0}^k (\sim w_i) 2^{64i} \\

&= \sum_{i=0}^k (2^{64}-1-w_i)2^{64i} \\

&= (2^{64}-1)\left(\sum_{i=0}^k 2^{64i}\right)-x \\

&= 2^{64(k+1)}-1-x\,.

\end{align*}

\]

(This makes sense, considering the binary representation for \(x\)).

Then

\[

y-x=y+(\sim x)+1 - 2^{64(k+1)}\,.

\]

Now if \(|y|> |x|\), then \(|y|-|x|=|y-x|\) (recall \(x\) and \(y\) have matching signs).

So we ignore signum entirely and suppose that \(x\) and \(y\) are positive.

In this case, \(y-x\) is positive since \(y> x\).

Supposing that we increase \(k\) to be one more than the word count of \(y\) by prepending zero words to \(x\), the sum \(y+(\sim x)+1\) is strictly less than \(2^{64(k+1)+1}\).

This means that \(y+(\sim x)+1\) must have a one in the binary \(2^{64(k+1)}\) place, lest \(y-x\) go negative.

We can therefore calculate \(y+(\sim x)+1\) and ignore the (guaranteed) carry into the \(2^{64(k+1)}\) place.

In the other case, where \(|y|< |x|\), we compute \(x-y\) instead, noting that \[ x-y=x+(\sim y)+1-2^{64(q+1)}\,, \] where \(q\) is the index of the most significant word in \(y\). Again, by increasing \(q\) to match \(k\), we can ignore the \(-2^{64(q+1)}\) term if we ignore the carry into the \(2^{64(q+1)}\) place in the sum \(x+(\sim y)+1\).

In practice, when we seek to mutate \(x\) to be \(x-y\), we add words to \(x\) via x.expand_to_subsume(y), which increases \(k\) to \(q\).

We then perform the addition \(x+(\sim y)\) or \(y+(\sim x)\) depending on x.abs_cmp(y), making sure to initialize the carry to 1 at the start to account for the missing \(+1\).

However, this addition occurs always in the word range \(w_0,w_1,\ldots, w_k\), ignoring the final carry.

When \(|y|> |x|\), this is as discussed; the (ignored) next word \(w_{k+1}\) would have received a final carry of one.

When \(|x|> |y|\), however, we were supposed to increase \(q\) to \(k\) (if necessary), then perform the addition on the words \(w_0,w_1,\ldots, w_q\).

This ostensibly differs from our procedure when \(q> k\).

However, recall that this cannot be the case from the expand_to_subsume call above; it must be that \(q\leq k\).

In addition, we'd like for \(y\) to remains const.

To work-around a y.expand_to_subsume(x) call, we virtually expand \(y\) when reading its words — if i < 0, we manually enforce y.word_r(i) == 0u (word_r is "word read-only").

/**

* Mutates this integer to be the sum (this + other).

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

exact::integer<n, ext>& exact::integer<n, ext>::add_local(const exact::integer<n, ext>& other){

// special cases for zero signum or matching signum

if(other.signum == 0){

return *this;

}

if(this->signum == 0){

*this = other.copy_remove_starting_zeros();

return *this;

}

if(other.signum == this->signum){

return this->add_local_matches_signum(other);

}

this->expand_to_subsume(other);

// the above expand_to_subsume call makes it so that

// 2^(64 * this->shift) divides both this and other.

// Since (alpha a - alpha b) = (a - b) alpha, we can do the subtraction

// as if the shift is zero.

//

// Note that ~a = 2^N - 1 - a, where N is one more than the power of two represented by

// the first bit of a->word(0).

// Then

// b - a = b + ~a + 1 - 2^N

// When |b| > |a|, b - a is positive so that (b + ~a + 1) has a 1 in the 2^N position, and we can just remove that 1

// to perform the subtraction (i.e., not carry the final 1).

// When |a| > |b|, we will instead produce

// a - b = a + ~b + 1 - 2^N

//

// Since |a - b| = |b - a|, these two subtractions will yield the same bitstring; we just have to be careful

// with signum.

//

// the + 1 will be implemented by an initial carry of 1

const std::strong_ordering cmp = this->abs_cmp(other);

if(cmp == std::strong_ordering::equivalent){

// the result will be zero, clear out this integer

while(this->word_count > 0){

this->pop_word();

}

this->signum = 0;

return *this;

}

// if true, this means that this < other, so we should compute other - this = other + ~this + 1 - 2^N

const bool this_tilde = ( cmp == std::strong_ordering::less );

const int32_t g0 = (this->word_count - other.word_count) + (this->shift - other.shift);

unsigned char carry = 1;

for(int32_t i = this->word_count - 1; i >= 0; --i){

const int32_t j = i - g0;

// virtual expansion of other.word_count to match this.word_count

uint64_t ob = j >= 0 && j < other.word_count ? other.word_r(j) : 0u;

if(!this_tilde){

ob = ~ob;

}

uint64_t& tb = this->word(i);

if(this_tilde){

tb = ~tb;

}

carry = _addcarry_u64(carry, ob, tb, &tb);

}

// If this_tilde == true, then |other| > |this|.

//

// We know that sign(this) != sign(other);

// If sign(this) == 1, then this > 0, other < 0, and this + other = |this| - |other|

// If sign(this) == -1, then this < 0, other > 0, and this + other = |other| - |this|

//

// So if...

// this_tilde && this.signum == 1, this + other = |this| - |other| and |other| > |this|, so this + other < 0

// this_tilde && this.signum == -1, this + other = |other| - |this| and |other| > |this|, so this + other > 0

// !this_tilde && this.signum == 1, this + other = |this| - |other| and |other| < |this|, so this + other > 0

// !this_tilde && this.signum == -1, this + other = |other| - |this| and |other| < |this|, so this + other < 0

this->signum = this_tilde == (this->signum == 1) ? -1 : 1;

this->remove_trailing_zero_words();

this->recompute_first_bit_offset();

return *this;

}

If this->signum == 0 or other.signum == 0, we return either this or other (copied); since the inputs are assumed to be well-formed representations, the output is as well.

If this->signum == other.signum, then the result of add_local_matches_signum correctly sets signum, first_bit_offset, and shift as discussed at the beginning of this section.

Otherwise, this->remove_trailing_zero_words() and this->recompute_first_bit_offset correctly sets signum, first_bit_offset and shift to maintain the maximum shift property and ensure the output is a valid representation.

Multiplication

Multiplication algorithms are extremely well researched. Unlike addition and subtraction, which have naive implementations matching the optimal \(O(n)\) runtime in the number of words involved, there exists multiplication algorithms which are better than the naive \(O(n^2)\) grade-school algorithm. These algorithms exploit patterns of repeated calculations done during expansion of the typical product \[ xy=\left(\sum_{i=0}^k w_i 2^{64i}\right)\left(\sum_{j=0}^q w_j' 2^{64j}\right)\,. \] As an example, let's consider \(k=q=1\). In this case, both \(x\) and \(y\) have two words, so we expect to perform four multiplications to account for the cross-terms \(w_0w_0'\), \(w_0w_1'\), \(w_1w_0'\), and \(w_1w_1'\). But by shelling out a few more cheap addition and bit-shifting operations, we can get away with only three multiplications: \[ \begin{align*} (w_0+2^{64}w_1)(w_0'+2^{64}w_1')&=w_0w_0'+2^{64}(w_0w_1'+ w_1w_0')+2^{128}w_1w_1' \\ &= w_0w_0'+ 2^{64}((w_0+w_1)(w_0'+w_1')-w_0w_0'-w_1w_0') + 2^{128}w_1w_1' \\ &= w_0w_0'(1-2^{64})+2^{64}(w_0+w_1)(w_0'+w_1')+w_1w_1'(2^{128}-2^{64}) \end{align*} \] (Note here that multiplication by \(1-2^{64}\) and \(2^{128}-2^{64}\) can be resolved by bit shifting operations and addition.) A slightly more general and recursive setup is the basis of the Karatsuba algorithm, which achieves \(O(n^{\log_2 3})\) runtime over the naive \(O(n^2)\).

For a product of 3-word numbers \(xy=(a+2^{64}b+2^{128}c)(d+2^{64}e+2^{128}f)\), there is a factorization with only five multiplications: \[ (a+2^{64}b+2^{128}c)(d+2^{64}e+2^{128}f)= \begin{bmatrix} 1+2^{63}-2^{128}-2^{191} \\ 2^{127}+\frac{1}{3}\left(2^{64}+2^{191}\right) \\ -2^{64}+2^{127}+2^{191} \\ \frac{1}{3}\left(2^{63}-2^{191}\right) \\ -2^{65}-2^{128}+2^{193}+2^{256} \end{bmatrix}^T \begin{bmatrix} ad \\ (a+b+c)(d+e+f) \\ (a-b+c)(d-e+f) \\ (a-2b+4c)(d-2e+4f) \\ cf \end{bmatrix} \] In addition to the five multiplications on the right, this involves bit shifting, a fairly substantial amount of addition, and (integer) division by three. This particular division by three can be done in linear time (like addition) via word-wise multiplication by the modular inverse of \(3\), together with some extra borrow bookkeeping. This family of factorizations leads to the Toom-Cook algorithm — or rather the special case Toom-3. In general, the Toom-\(n\) algorithm provides a standard method to rewrite the product \(\left(\sum_{i=0}^n w_i 2^{64i}\right)\left(\sum_{j=0}^n w_j' 2^{64j}\right)\) with only \(2n-1\) multiplications. When made into a recursive algorithm, Toom-\(n\) has significantly better asymptotic runtime than the naive method.

The last major practical multiplication algorithm is the famed Schönhage-Strassen algorithm, which uses the fast Fourier transform (FFT) to convert the convolution \(xy\) into a point-wise multiplication.

There is an exceptionally nice unifying structure for Karatsuba, Toom-Cook, Schönhage-Strassen and other related algorithms that shows that the Chinese remainder theorem is really to thank for the algorithmic improvements. Our single iteration of Toom-3 above, for example, is a chain \[ \begin{align*} \mathbb{Z}\to \mathbb{Z}[x]/(2^{64} - x)\to \mathbb{Z}[x]\to\mathbb{Z}[x]/(x^4+2x^3-x^2-2x)\cong \prod_{j=-1}^2\mathbb{Z}[x]/(x-j) \\ y\mapsto\sum_{i=0}^2\alpha_i 2^{64i}\mapsto\sum_{i=0}^2\alpha_ix^i\mapsto\left(\sum_{i=0}^2\alpha_i(-1)^i,\sum_{i=0}^2\alpha_i(0)^i,\ldots,\sum_{i=0}^2\alpha_i(2)^i\right)\quad\, \end{align*}\,.\] In the quotient ring \(\prod_{j=-1}^2\mathbb{Z}[x]/(x-j)\), multiplication is point-wise. For a dense but accurate explanation, see Bernstein's "Multidigit Multiplication for Mathematicians".

This is all very interesting, but if we look at GMP's threshold for applying Toom-2 (aka Karatsuba) over the naive school algorithm, it's something around 20 words per operand. We expect very few calculations to make it to 20 words of precision, if any. Therefore we will content ourselves with implementing the naive algorithm, and Karatsuba's algorithm, just in case.

We'd expect a straightforward implementation for the naive, nested loop multiplication algorithm. It does appear simple, though there are some hidden details that we'll have to work out.

/**

* Computes the multiplication a * b using the naive grammar-school method,

* storing the result in "store".

*

* a_word_min must be the index of the first word in a (from the left) that contains a non-zero digit.

*

* b_word_min must be the index of the first word in b (from the left) that contains a non-zero digit.

*

* store must contain at least (a.word_count - a_word_min) * (b.word_count - b_word_min) words, all initialized to zero.

*/

template<int n, bool ext>

void exact::mult_school(const exact::integer<n, ext>& a, const int32_t a_word_min,

const exact::integer<n, ext>& b, const int32_t b_word_min,

exact::integer<n, ext>& store){

uint64_t low, hi;

unsigned char carry {0}, hi_carry {0};

int32_t tb {store.word_count - 1};

for(int32_t i {a.word_count - 1}; i >= a_word_min; --i){

const uint64_t ab = a.word_r(i);

for(int32_t j {b.word_count - 1}; j >= b_word_min; --j){

uint64_t& store_lo {store.word(tb)};

uint64_t& store_hi {store.word(tb - 1)};

low = _mulx_u64(ab, b.word_r(j), &hi);

carry = _addcarry_u64(0, low, store_lo, &store_lo);

hi_carry = _addcarry_u64(carry, hi + hi_carry, store_hi, &store_hi);

--tb;

}

tb += b.word_count - b_word_min;

--tb;

}

store.shift = a.shift + b.shift;

store.signum = a.signum * b.signum;

store.remove_trailing_zero_words();

store.recompute_first_bit_offset();

}

First, let's look at indexing.

The outer loop iterates over all words of a from least to most significant.

The inner loop iterates over all words of b from least to most significant.

tb is the index of the lower-significance destination word in store (the product of two one-word numbers takes up at most 2 words).

The initial value of tb is the last (least significant) word in store, since the first product of words is the least significant from both a and b.

Every time we move to the left (increasing significance) in b, keeping the a word constant, we increase the significance in the destination by 1 word.

The actual computation happening here is

\[

\left(\sum_{i=0}^k w_i2^{64i}\right)\left(\sum_{j=0}^q w'_j2^{64j}\right)=

\sum_{i=0}^k\sum_{j=0}^q(w_iw_j')2^{64(i+j)}\,.

\]

As \(j\) increases while \(i\) stays the same, our factor \(2^{64(i+j)}\) increases by 64 bits, or one word.

Now when we increment the word in \(a\) (change \(i\) in the loop), the factor \(2^{64(i+j)}\) drops by \(64(q-1)\), since \(j\) is reset to zero and \(i\) increments.

This is reflected in the following lines from above, noting the adjustment for leading zero words in b.

tb += b.word_count - b_word_min;

--tb;

Next, let's talk about carrying.

There are two carrying variables, carry and carry_hi.

\[

\begin{array}{rl}

s_{t+3}\quad s_{t+2}\quad s_{t+1} {\color{red}{\curvearrowleft}} s_t \quad \ldots \quad s_0 \\

+\qquad\qquad\quad{\color{green}{\swarrow}}\, r_{\text{hi}}\quad\,\,\, r_{\text{lo}}\qquad\qquad\, \\

\hline

s_{t+3}\quad s_{t+2}{\color{red}{\curvearrowleft}} s_{t+1}'\quad s_t'\quad\ldots\quad s_0 \\

+\qquad\,\,{\color{green}{\swarrow}}\,r_{\text{hi}}'\quad\,\,\, r_{\text{lo}}'\qquad\qquad\qquad\quad\! \\

\hline

s_{t+3}\quad s_{t+2}''\quad s_{t+1}''\quad s_t'\quad \ldots\quad s_0

\end{array}

\]

carry stores the extra bit overflow from the sum low + store_low, i.e. the lower-significance word in the product \(w_i w_j'\) and the target store word.

Above, this is represented by the curved, red arrow in the sums \(r_{\text{lo}}+s_t\) and \(r_{\text{lo}}'+s_{t+1}'\).

This carry is absorbed into the high half sum, hi + store_hi, represented in the diagram as the sums \(r_{\text{hi}}+s_{t+1}\) and \(r_{\text{hi}}'+s_{t+2}\).

This high half sum may also have an overflow bit, which we put into carry_hi.

The reason that we need two carry flags, is that the high half sum may need to absorb two different carries, one from the carry from the low significance sum, and one carry_hi from the high significance sum from the previous iteration in the inner loop.

The high carries are represented by green arrows in the diagram.

One results from the sum \(r_{\text{hi}}+s_{t+1}\) and is absorbed in the \(r_{\text{hi}}'+s_{t+2}\) sum, and the other results from the sum \(r_{\text{hi}}'+s_{t+2}\) and is absorbed later (not shown).

The dual carry absorption results in an unconventional looking line:

hi_carry = _addcarry_u64(carry, hi + hi_carry, store_hi, &store_hi);carry occupies the usual carry slot, we simply add hi_carry to the high-significance product hi.

Should we not be concerned about overflow in the sum hi + hi_carry?

Well, recall that hi is bits 64-127 (zero-indexed) of the product of two 1-word numbers.

The maximal product of two 1-word numbers is

\((2^{64}-1)^2 = 2^{128}-2^{65}+1\) which has high half

\[\left\lfloor\frac{2^{128}-2^{65}+1}{2^{64}}\right\rfloor=\lfloor2^{64}-2+2^{-64}\rfloor=2^{64}-2\,.\]

Thus hi can always accommodate a hi_carry of maximum value \(1\).

The next slightly suspicious item is that while carry is reset every iteration of the inner loop, hi_carry is not reset even when the outer loop increments.

It's fairly clear that hi_carry ought to be zero whenever the inner loop starts over, yet it appears to retain whatever value it had last, which ostensibly could be one.

However, because of the order from least-to-most significant in both the inner and outer loop, the hi_carry will always be zero upon completion of the last iteration of the inner loop.

After the inner loop completes its j == b_word_min iteration, store contain the partial sum, for some \(N\leq q\), except for possibly a hanging carry from carry_hi,

\[

\begin{align*}

\sum_{i=0}^N\sum_{j=0}^q(w_iw_j')2^{64(i+j)}&\leq \sum_{i=0}^N\sum_{j=0}^q (2^{64}-1)^22^{64(i+j)} \\

&\leq (2^{64}-1)^2\sum_{i=0}^N 2^{64i}\sum_{j=0}^q 2^{64j} \\

&\leq (2^{64}-1)^2\sum_{i=0}^N 2^{64i}\frac{2^{64(q+1)}-1}{2^{64}-1} \\

&\leq (2^{64}-1)(2^{64(q+1)}-1)\sum_{i=0}^N 2^{64i} \\

&\leq (2^{64(q+1)}-1)(2^{64(N+1)}-1)\,.

\end{align*}

\]

Now this product is less than \(2^{64(q+N+2)}\), which means that the store word \(s_{q+N+2}\) is zero.

The store word \(s_{q+N+1}\) has the same significance as store_hi in the final iteration of the inner loop.

This means that there is never a carry in the sum (hi + hi_carry) + store_hi, and carry_hi is set to zero at the end of this loop iteration.